Chapter 5 Gender patterns of publication in top sociology journals22

Abstract

This article examines publication patterns over the last 70 years from the American Sociological Review and American Journal of Sociology, the two most prominent journals in sociology. We reconstructed gender of all published authors, identified article contents and collected data on citations. We reconstructed each author’s academic pedigree. Results suggested that these prestigious journals especially considered male authors and their exclusive co-authorship ties. These gender penalties persist even when looking at citations and after controlling for the influence of academic affiliation.

Keywords: “Sociology, Journals, Gender, Co-authorship, Inequality”

5.1 Introduction

The construction of academic reputation is a complex organizational process in which the publishing system has a major role (Clemens et al. 1995). Although academic careers depend on complex factors, publications are key for tenure and promotion (Leahey, Keith, and Crockett 2010; Long 1992; Grant and Ward 1991). In an era of “publish or perish” hyper-competition, even funding agencies heavily rely on bibliometric indicators, such as the number of publications and citations, to allocate grants (Edwards and Roy 2017; Nederhof 2006). As such, understanding publication patterns in prestigious journals can help reveal possible sources of inequality in academic credit allocation.

Indeed, previous research showed that while prestigious journals determine stratification processes, which shape standards of performance and identity of a discipline, in a context of excessive competition, their elitism could penalize innovation, reduce academic diversity and favor inertia. For instance, in a study on top sociology journals in 1987-88, Clemens et al. (1995) found that women rarely appeared among the rank of most prolific authors and productivity and reputation could be even orthogonal to one another (see also Karides et al. (2001)). In a recent study on publications in 2000-2015, Teele and Thelen (2017) found that women are disproportionately under-published in top political science journals. They found that the largest percentage of publications were dominated by all-male teams, with women less involved in co-authorship networks. They suggested that this could be due to a self-selection process. Given that women may be attracted more by qualitative research, also due to structural discrimination in higher education and considering that these journals are predominantly quantitative, they would therefore submit less to these top journals.

The fact that there are gender differences in academic success despite the rise of women in science is well-known (Cole and Zuckerman 1984, 1987; Young 1995). Research suggested that women are penalized especially in STEM research (Cain and Leahey 2014; Lomperis 1990; Kahn 1993; Sheltzer and Smith 2014), are paid less (Prpić 2002) and are preferably hired in lower level academic positions and in less prestigious institutes (Lomperis 1990; Heijstra, Bjarnason, and Rafnsdóttir 2015). They publish fewer papers and are cited less (e.g., Xie and Shauman (1998); Young (1995); Maliniak, Powers, and Walter (2013)).

On the one hand, this may be due to gender differences in scientific collaboration patterns and attitudes. Firstly, research suggests that women tend to establish more homogeneous and smaller collaboration networks (Grant and Ward 1991; Renzulli, Aldrich, and Moody 2000). This would decrease their chance to be part of the core network of star scientists (Moody 2004). Secondly, they prefer more diversified research programs and so their research is less specialized, penalizing their visibility and success (Leahey 2006, 2007). This could decrease their access to relevant resources for funding and promotion (Xie and Shauman 1998; Weisshaar 2017) and make their academic career less stable or rewarding (Hancock and Baum 2010; Preston 1994), also due to distortion from hiring committees due to family obligations (Rivera 2017).

On the other hand, there are reflexive constructive processes in which gendered patterns could be internalized by women (e.g., Ridgeway (2009); MacPhee, Farro, and Canetto (2013); Brink and Benschop (2014)). For instance, even when women are motivated to pursue an academic career, they have lower expectations of success (Prpić 2002; Fox and Stephan 2001; Leslie et al. 2015). This can be due to what Cech et al. (2011) p 642 called “professional role confidence”, i.e., “individuals’ confidence in their ability to fulfill the expected roles, competences, and identity features of a successful member of their profession”. Not only can these socially shared beliefs contribute to gendered persistence in male-dominated professions; they build-in gender penalties via self-reinforcing processes. This was confirmed even by a recent lab experiment, where subjects were asked to evaluate a sample of comparable academic articles in terms of quality, clarity, significance and methodological rigor. Articles published by women receive lower evaluations even by female evaluators (Krawczyk and Smyk 2016).

It is important to note that these aspects have important implications. While the under-representativeness of women calls for a response for equity, research on natural and cultural evolution has indicated that diversity is key for adaptation, learning and resilience in any complex system (e.g., Page (2010)). Given that science is a self-organized and decentralized complex system, gender penalties could create an institutional context that reduces cultural and epistemic heterogeneity and diversity (Belle, Smith-Doerr, and O’Brien 2014). This could have negative implications on collective learning and experimentation. This is even more so in sociology, which does not have a consensual epistemological or methodological standard (Dogan and Pahre 1989). It is therefore not surprising that in a recent review on diversity in working teams of scientists, Nielsen et al. (2017) found that more gender, ethnically or culturally diverse teams performed better. Misra et al. (2017) suggested that active inclusion of minorities tend to promote innovation, creativity, and positive reputational effects especially when teams are integrated.

In this chapter, we wanted to provide an overview of gender publication patterns in top journals in sociology, i.e., the American Sociological Review (hereafter ASR) and the American Journal of Sociology (hereafter AJS) (Leahey 2007; Light 2013). Not only do these two journals constitute the elite of our discipline, in a stratified publication market where competition, control and boundaries are strong (some critics have even considered these journals as “alleged cartels”, see Platt (2016)); they also are different in their historical origins, which trace back to the schism among ASA members in 1935, with AJS becoming the journal of an independent, prestigious department (Chicago) and ASR embedded in a representative association (e.g., Lengermann (1979); Abbott (1999)).

While previous research suggests that sociology is probably less gender biased than other disciplines, due to more women graduates (Lutter and Schröder 2016), it is probable that tenure tracks and promotion in the academic élite is more competitive (Light 2009), due to the influence of symbolic capital in academic success (Bourdieu 1988). This would suggest that looking at the top could reveal gender patterns of inequality, which weak competitiveness in lower academic layers could obscure. Furthermore, given that competitive pressure for publication is higher in these top journals, looking at the top could reveal general trends in hyper-competitive science today.

To do so, we followed a recent study by Teele and Thelen (2017) on a sample of political science journals in the data collection strategy, while paying attention to academic affiliations over a longer time scale. In addition, we applied advanced machine learning techniques on article contents and integrated data on publications with available web data on authors’ academic pedigree to understand whether academic affiliation or research contents could contribute to inequalities in publishing.

The rest of the chapter is organized as follows: Sect 2 presents our data, while Sect 3 presents our descriptive results. Sect 4 presents an analysis of article contents, while Sect 5 presents some more advanced statistical models. Finally, Sect 6 summarizes our main findings and discusses limitations and further developments of our work.

5.2 Dataset

Data on all AJS and ASR publications were extracted from Scopus on 20th January 2017, and included article title, authors’ names and affiliation, and number of citations received. Table 5.1 shows the time range of publications in each of these journals.

| Journal name | # papers | Sample Starts | Sample Ends |

|---|---|---|---|

| American Journal of Sociology | 1,153 | 1946 | 2016 |

| American Sociological Review | 1,440 | 1965 | 2016 |

| Total number of papers | 2,593 |

|

|

In order to check for authors’ gender, we used authors’ first names to send automatic requests with R scripts to a database of numerous names extracted from social media profiles (Wais 2016). Simultaneously a research assistant (hereafter RA) hand-coded author gender. In any conflicting attribution case, the RA researched the online profile of authors, whenever available. We then matched the gender extracted from API23 with the hand-coded one. In any cases of differences (41 out of 2,897 authors), we used the hand-coded gender. In cases of missing data in the hand-coded procedure (22 out of 2,897 authors), we used the automatic gender extracted from API, which was based on accuracy percentages (note that we had only 17 out of 2,897 missing genders).

As suggested by Young (1995), Maliniak, Powers, and Walter (2013) and Teele and Thelen (2017) we coded any article as written by Solo male, Solo female, All male team, All female team, and Cross gender collaboration. Furthermore, following Karides et al. (2001) and Teele and Thelen (2017), we used the American Sociological Association (hereafter ASA) annual membership as a proxy of the gender composition of the community24.

In order to add some control variables, we also checked the CV and online information of each author. This allowed us to identify the academic institution that awarded each scientist’s PhD title. We also looked at the current gender composition of the first 12 top ranked Ivy-League sociology departments in the Shanghai ranking, by extracting data from the official websites25. These variables were used to estimate whether women could potentially benefit differently from an Ivy-League effect in the publication process.

5.3 Descriptive Results

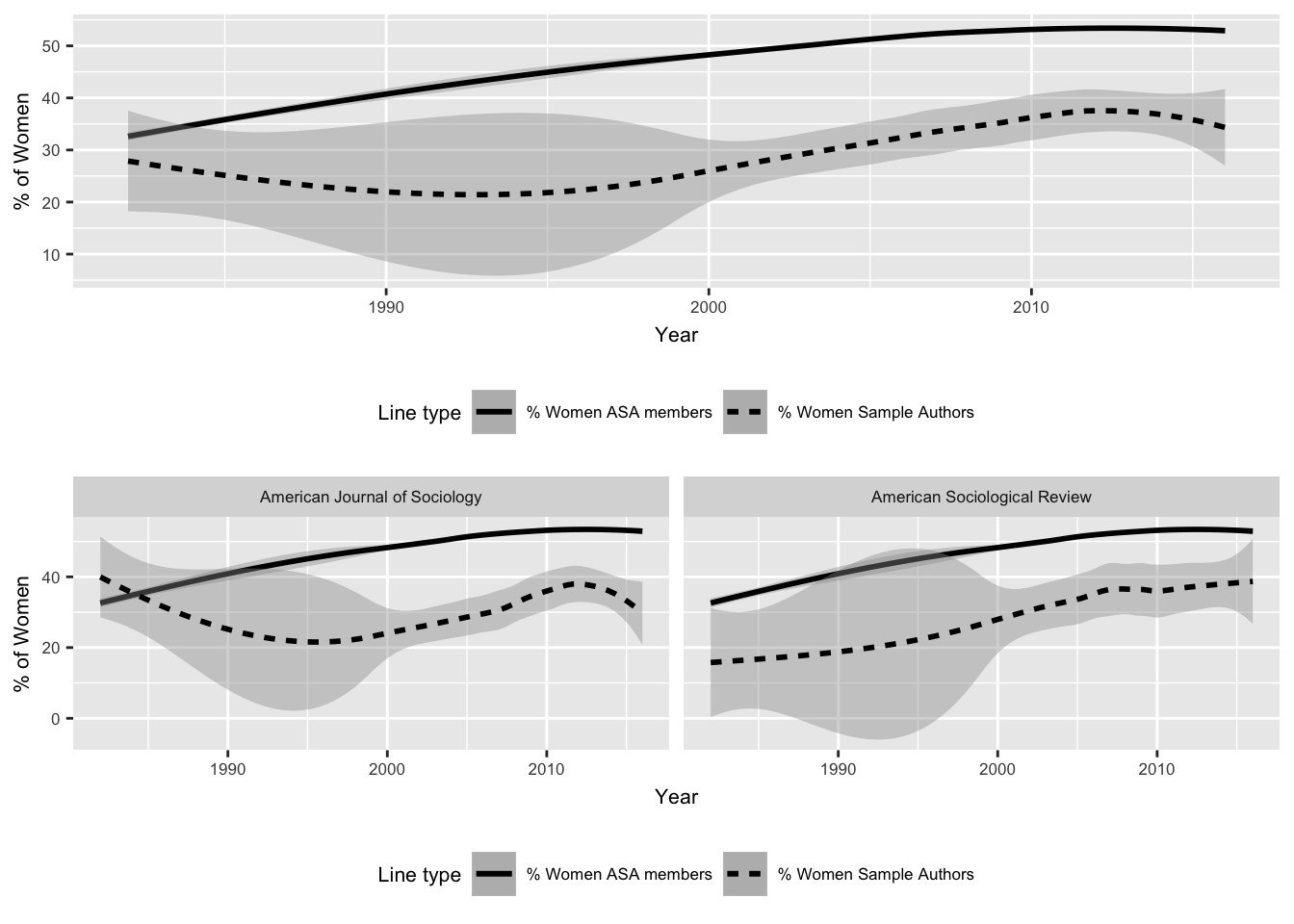

Figure 5.1 shows the historical trend of the percentage of women who authored an article in AJS and ASR and in both journals, compared to the percentage of women who were ASA members (continuous line). Considering only the last year of our sample, 2016, while women were more among ASA members (53%), the gender balance among authors in AJS and ASR approximated a 70(men)/30(women) ratio. Although the two journals showed different dynamics and since 2000 the gender gap has been reducing, it would take more than ten years to reach a fair gender balance (if perhaps unstable) at the current rate.

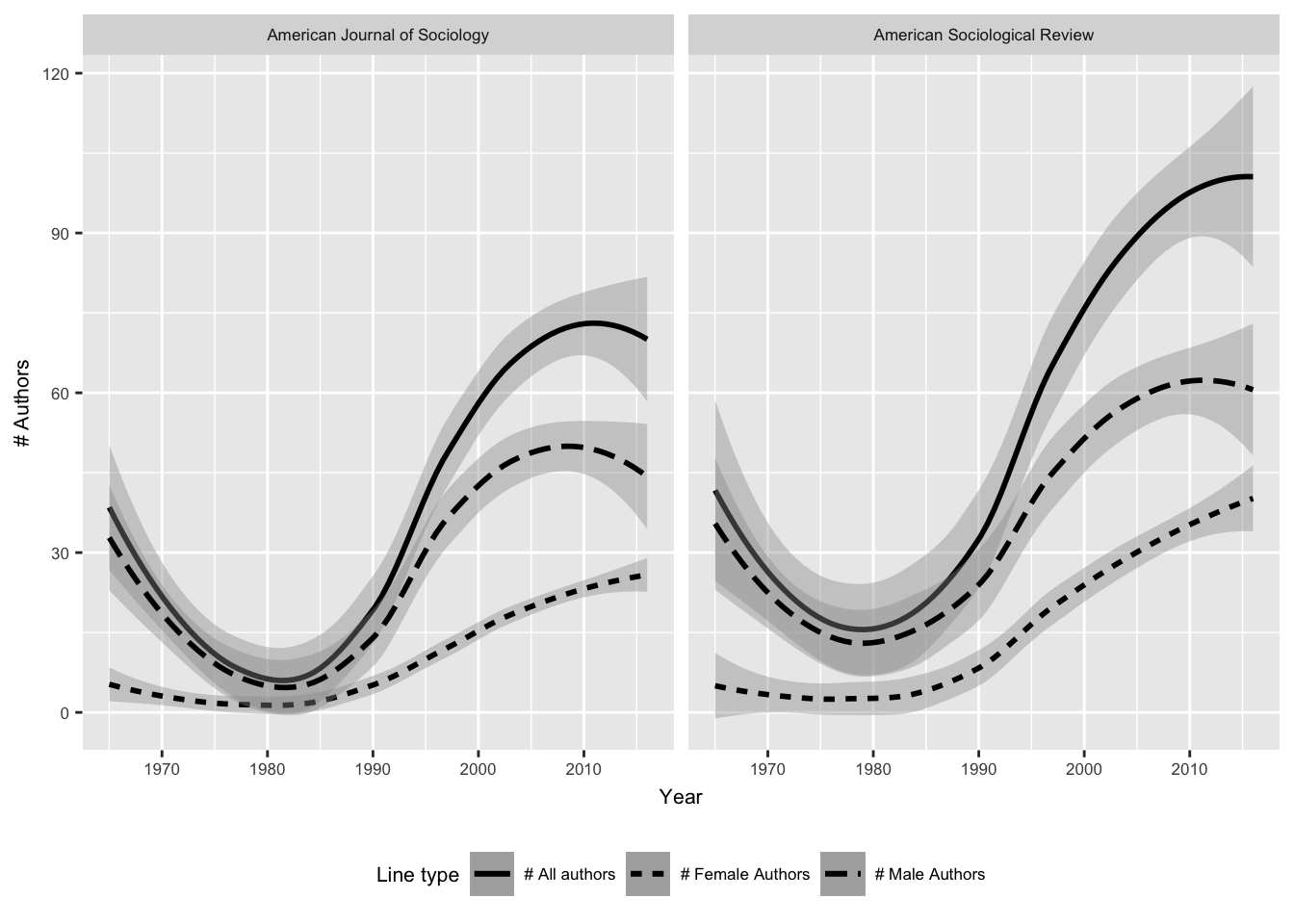

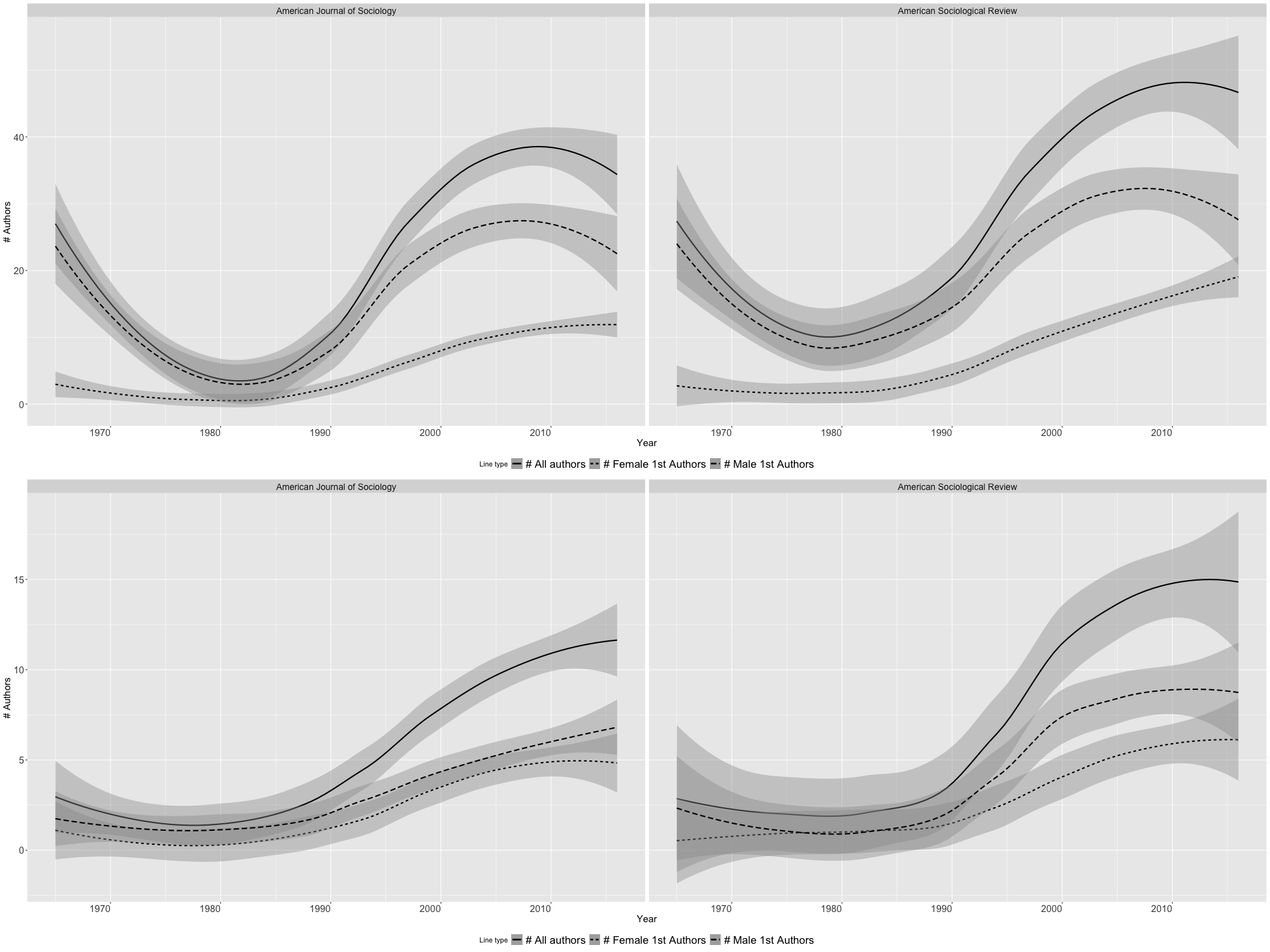

Although the number of authors has increased over time (e.g., Wuchty, Jones, and Uzzi (2007)), which could be simply due to the increased number of articles published in these journals yearly, Figure 2 shows that the number of women who published in AJS and ASR tended to increase less than men.

Figure 5.1: Percentage of women among authors in AJS and ASR (dashed lines) compared to percentage of ASA female members over time (continuous lines). At the top, the aggregate trend, at the bottom the trend per journal. Data are based on a t-test of the distributions. The grey zone indicates the confidence interval of the two lines.

When considering co-authorship patterns, we found that while 84% of articles published in AJS and ASR had at least one (or more) male author(s), only 40% of these had at least one (or more) female author(s). In general, the picture approximates a 70/30 ratio, which is slightly better than what suggested by Young (1995)’s study in political science but similar to what found more recently by Teele and Thelen (2017) (see Table 5.2). Although norms and practices of collaboration might be context-specific, it seems that fields such as sociology and political science do not dramatically differ in terms of gender collaboration patterns.

Figure 5.2: Gender trend of authorship in AJS and ASR

| Journal Name | # All Papers | # All Authors | # Men | % Men | # Women | % Women |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AJS | 1,153 | 2,023 | 1,469 | 72.61 | 547 | 27.04 |

| ASR | 1,440 | 2,686 | 1,860 | 69.25 | 813 | 30.27 |

| Total number | 2,593 | 4,709 | 3,329 |

|

1,360 |

|

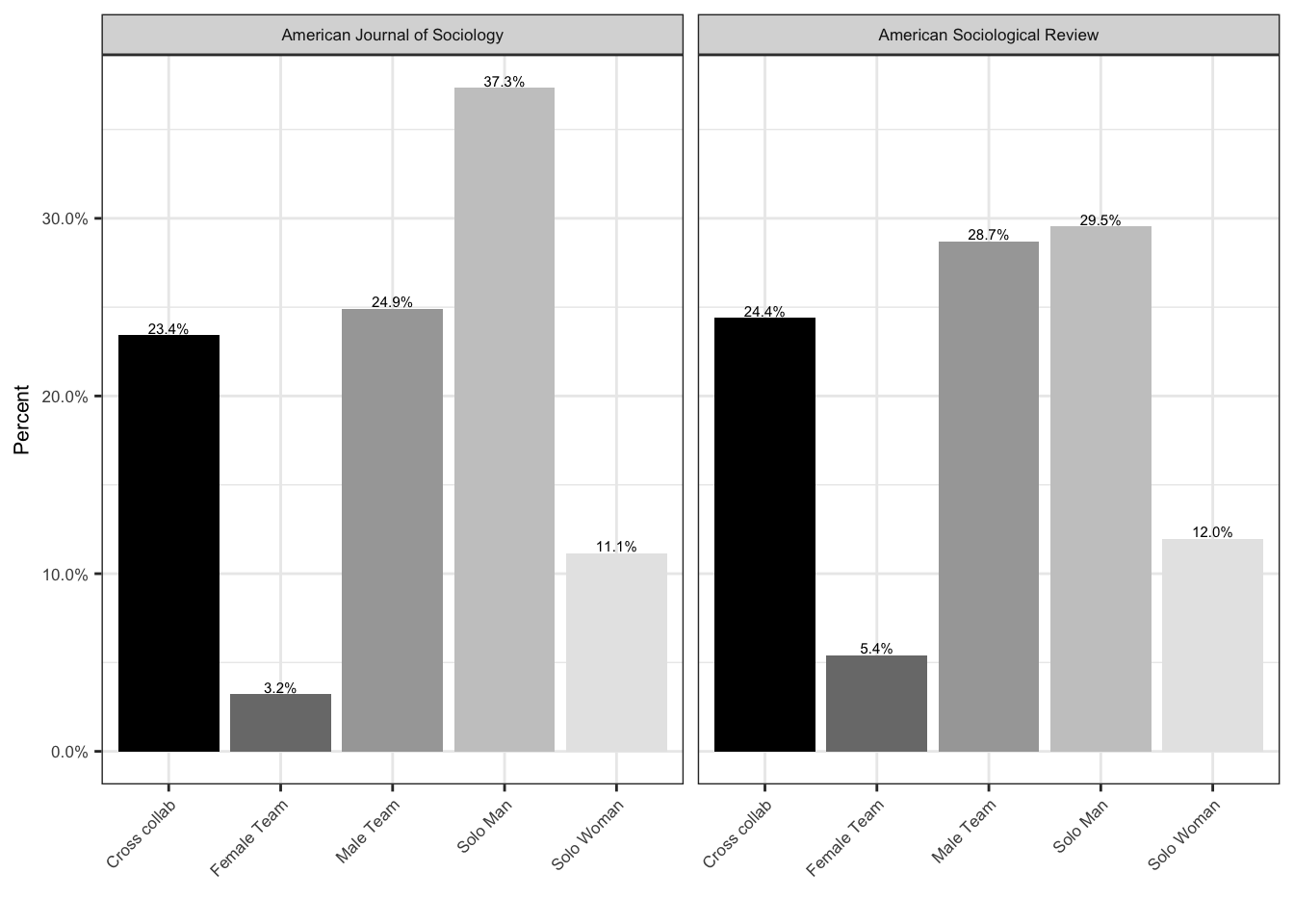

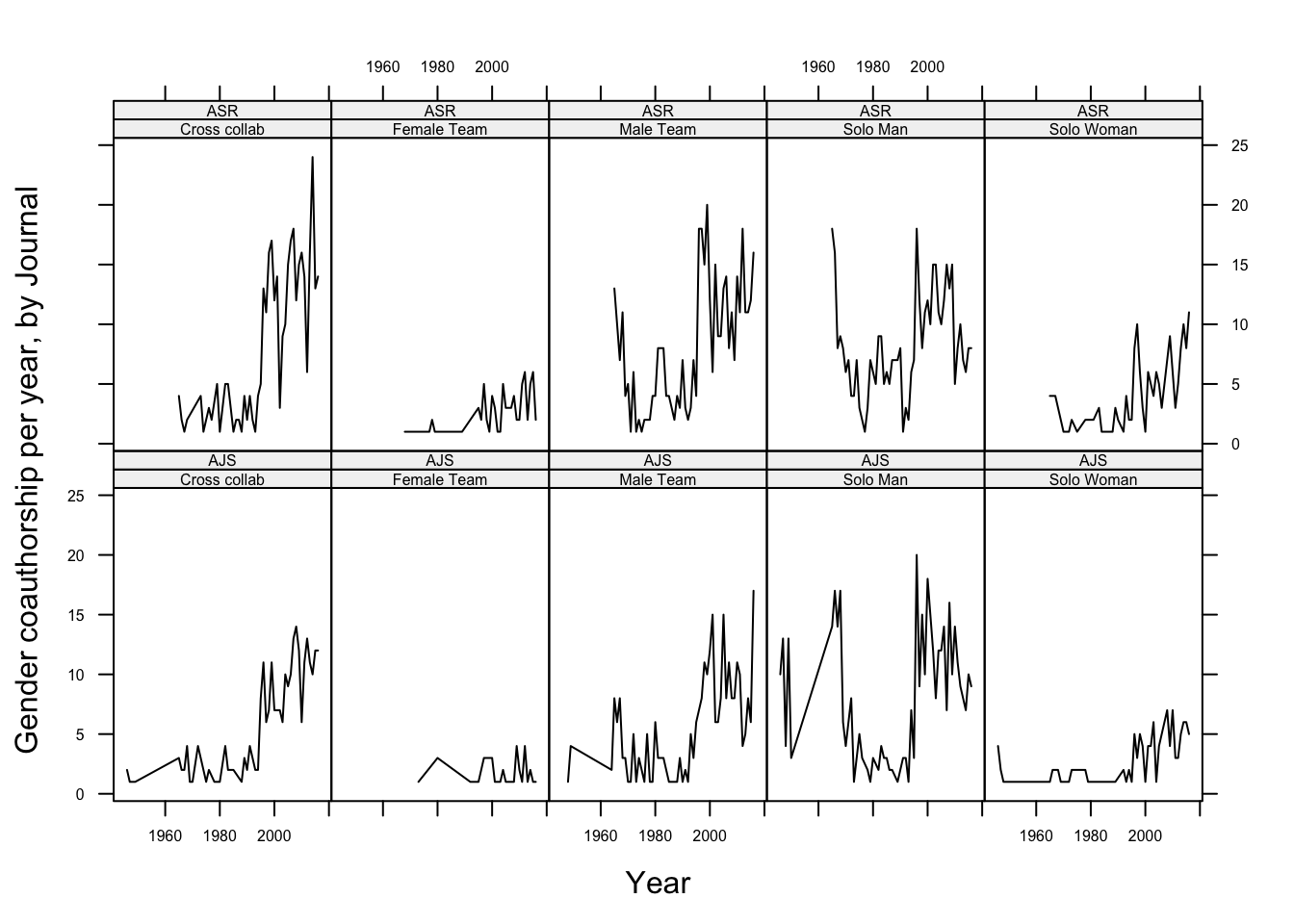

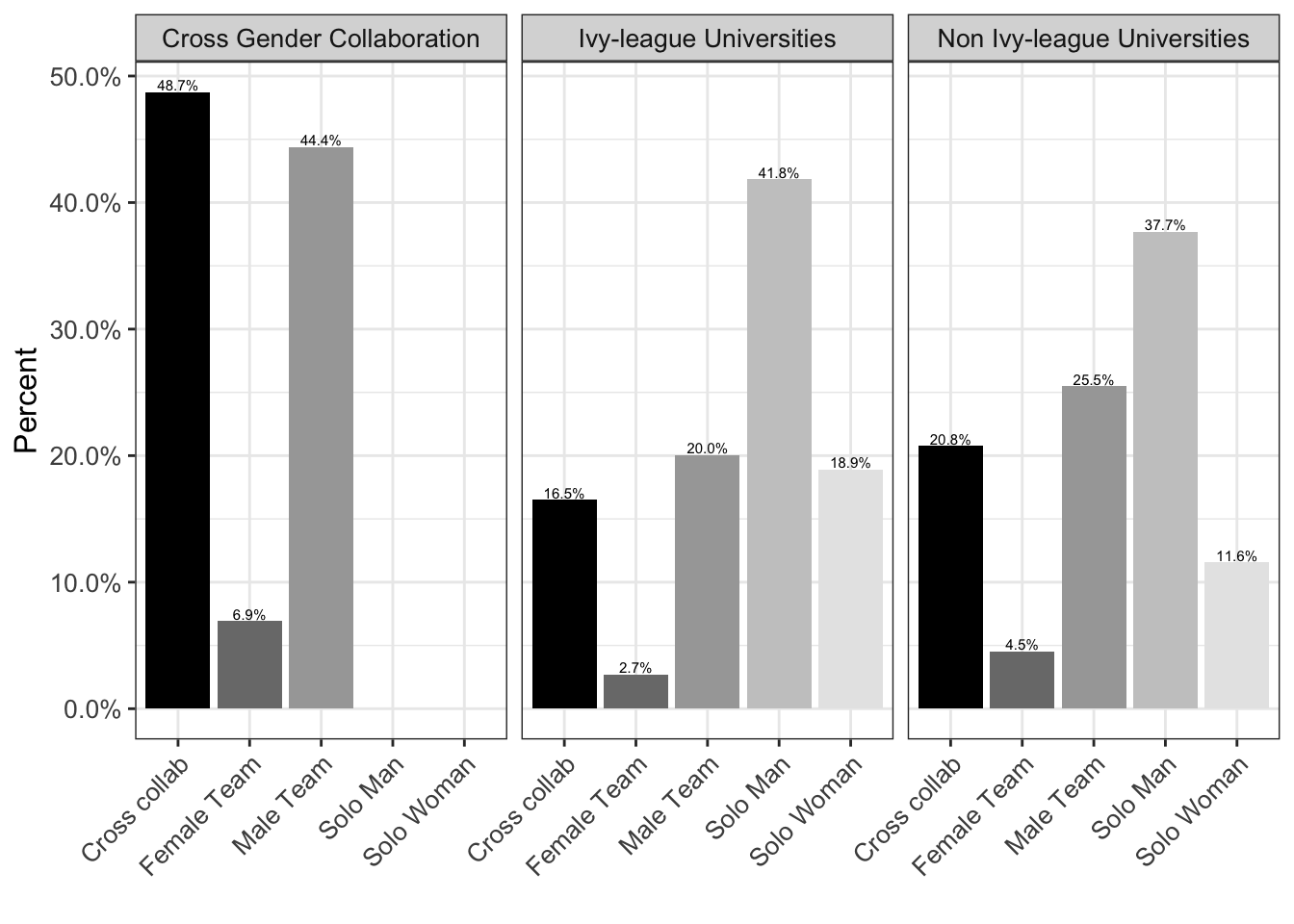

More specifically, Figure 5.3 shows that in both journals, only 11% of articles were published exclusively by solo women against 37% in AJS and 29.5% in ASR of solo male. Furthermore, only 5.4% of articles in ASR and 3.2% in AJS were published by all-female coauthor teams. However, Figure 5.4 shows that cross-gender co-authorship increased at least recently.

Figure 5.3: Gender co-authorship in AJS and ASR

Figure 5.4: Gender co-authorship dynamics in AJS and ASR

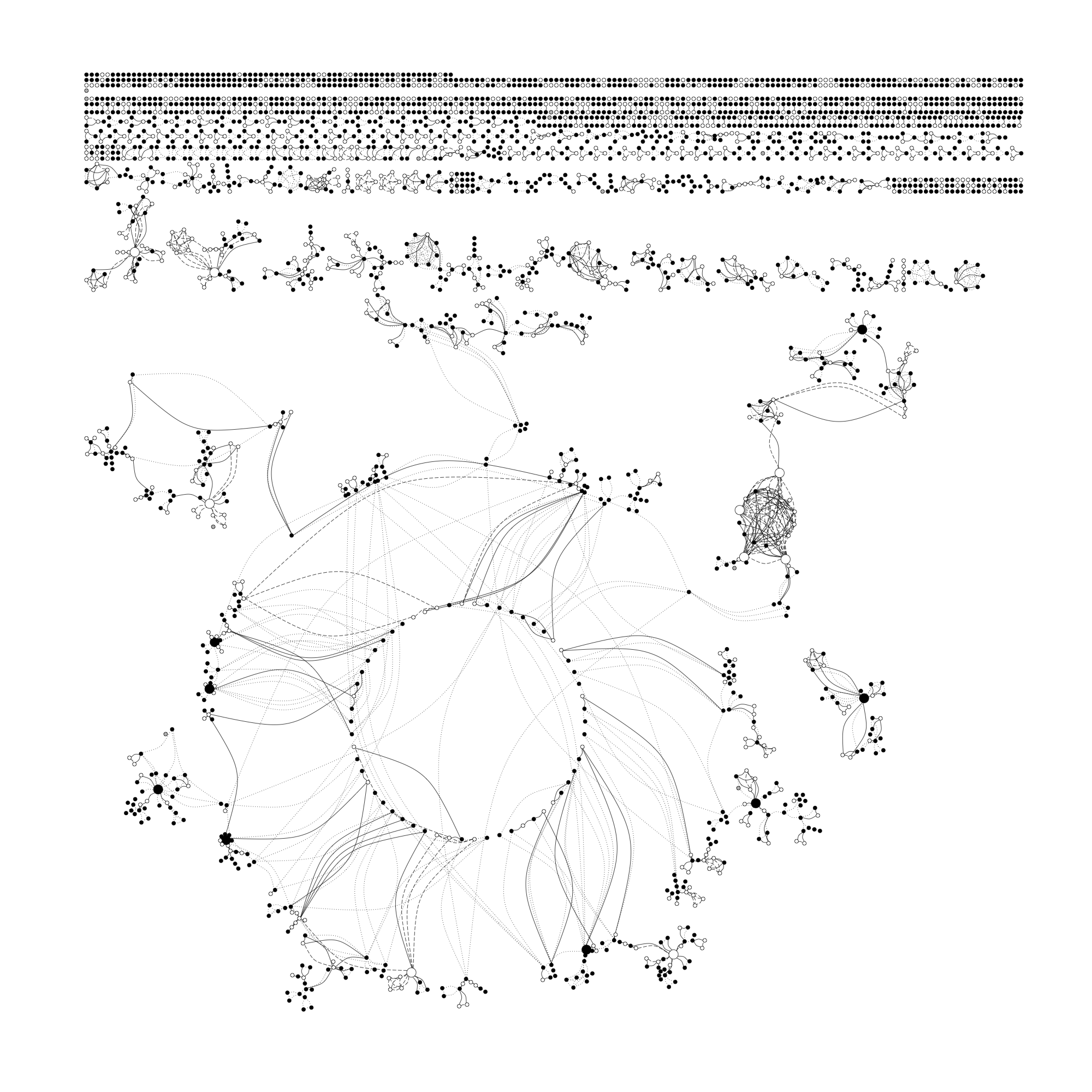

Figure 5.5 shows that women are first authors of these articles less frequently than men and that inequalities in author positions did not significantly change over time. The trend is similar in the case of cross-gender collaboration (see the bottom panel). Indeed, the first authors of mixed-gender teams were predominately men, with only a few exceptions for certain years in ASR in which first authorships were more gender balanced. Figure 6 shows the co-authorship networks in these two journals. While results indicate the co-existence of different clusters of more or less influential connections, it is rare that women are in central positions in these networks. Table 5.3 shows that the network of co-authorships was fragmented (i.e., high number of disconnected, small sized clusters) and included half of edges formed exclusively between men (48.15%), 35.41% cross-gender and only 15% exclusively between women.

Figure 5.5: Gender difference in first authorship in in AJS and ASR. At the top, the aggregate trend of all publications, at the bottom the specific trend of cross-gender coauthored articles.

| Metric | Value |

|---|---|

| Number of nodes | 2897 |

| number of edges | 2787 |

| Number of female authors | 936 |

| Number of male authors | 1944 |

| Men to men edges | 48.15 |

| Men to women edges | 35.41 |

| Women to women edges | 15.5 |

| Density | 0.0007 |

| Diameter | 46 |

| Number of clusters | 1084 |

| Cluster size (avg) | 2.67 |

| Cluster size (std) | 19.72 |

Figure 5.6: Gendered co-authorship networks (nodes are authors, ties are authoring articles together). Black indicates males, white indicates females. Solid ties are cross-gender, dotted within males and longdashed within females. Node size indicates an author’s importance, i.e., his/her degree centrality. The higher the importance is, the bigger the nodes are.

We then looked at more sophisticated network characteristics, such as betweenness, triangles, and network degree. One of the main centrality measures used in network analysis, betweenness reflects the importance of a node to mediate a network’s structure (i.e., it represents the number of times a node is positioned on the shortest paths between any pairs of nodes in a network) (Wasserman and Faust 1994 p 189). As regards to triangles, it is important to note that an important aspect of any social network compared to random networks is the tendency of actors to close their mutual connections. In our cases, triangles represent the tendency of scientists to write articles with collaborators of their coauthors more than with other potential collaborators (Luke 2015 p 16). Finally, network degree represents another measure of the importance of an actor in a network. In our cases, we considered the number of coauthorship ties any author had (Wasserman and Faust 1994 p 178).

By looking at these network metrics, we found that top women had higher degrees (6 out of top 10 authors) and more inclined to building triangles among authors (i.e., they co-authored more frequently with co-authors of their previous co-authors). However, this gave women neither an advantage in terms of number of publications nor more recognition and citations (see Table 5.4). This confirms research on the misalignment between co-authorship network positions of scientists and prolificacy and success (Grimaldo, Marušić, and Squazzoni 2018).

| Betweenness | More prolific | More cited | Triangles | Degree |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Roscigno (M) | Bearman (M) | Uzzi (M) | Kelly (W) | Moen (W) |

| Baumer (M) | Massey (M) | Sampson (M) | Moen (W) | Kelly (W) |

| Qian (M) | Gove (M) | Portes (M) | Kossek (W) | Land (M) |

| Jacobs (M) | Rao (W) | Massey (M) | Casper (W) | England (W) |

| O’brien (M) | Crowder (M) | Meyer (M) | Okechukwu (W) | Logan (M) |

| King (M) | Tolnay (M) | Emirbayer (M) | Mierzwa (M) | Kossek (W) |

| Martin (M) | Logan (M) | Thomas (M) | Hanson (W) | DiPrete (M) |

| Dixon (M) | DiPrete (M) | Boli (M) | Davis (W) | Pescosolido (W) |

| Messner (M) | Jacobs (M) | Ramirez (M) | Hammer (W) | McCammon (W) |

| Carroll (M) | Firebaugh (M) | Podolny (M) | Oakes (M) | Hannan (M) |

Figure 5.7 shows that women had only a 21.5% premium in terms of higher probability of publishing in AJS and ASR when they were a member of a prestigious sociology department, against a 62% premium for men. Interestingly, cross-gender collaboration was more frequent among members of less prestigious departments (20.8% vs. 16.5%). Furthermore, the number of all-female teams of authors was higher when they included only females working in non-Ivy-League departments (4.5% vs. 2.7%).

Figure 5.7: Gender co-authorship dynamics between Ivy and non Ivy-League authors in AJS and ASR

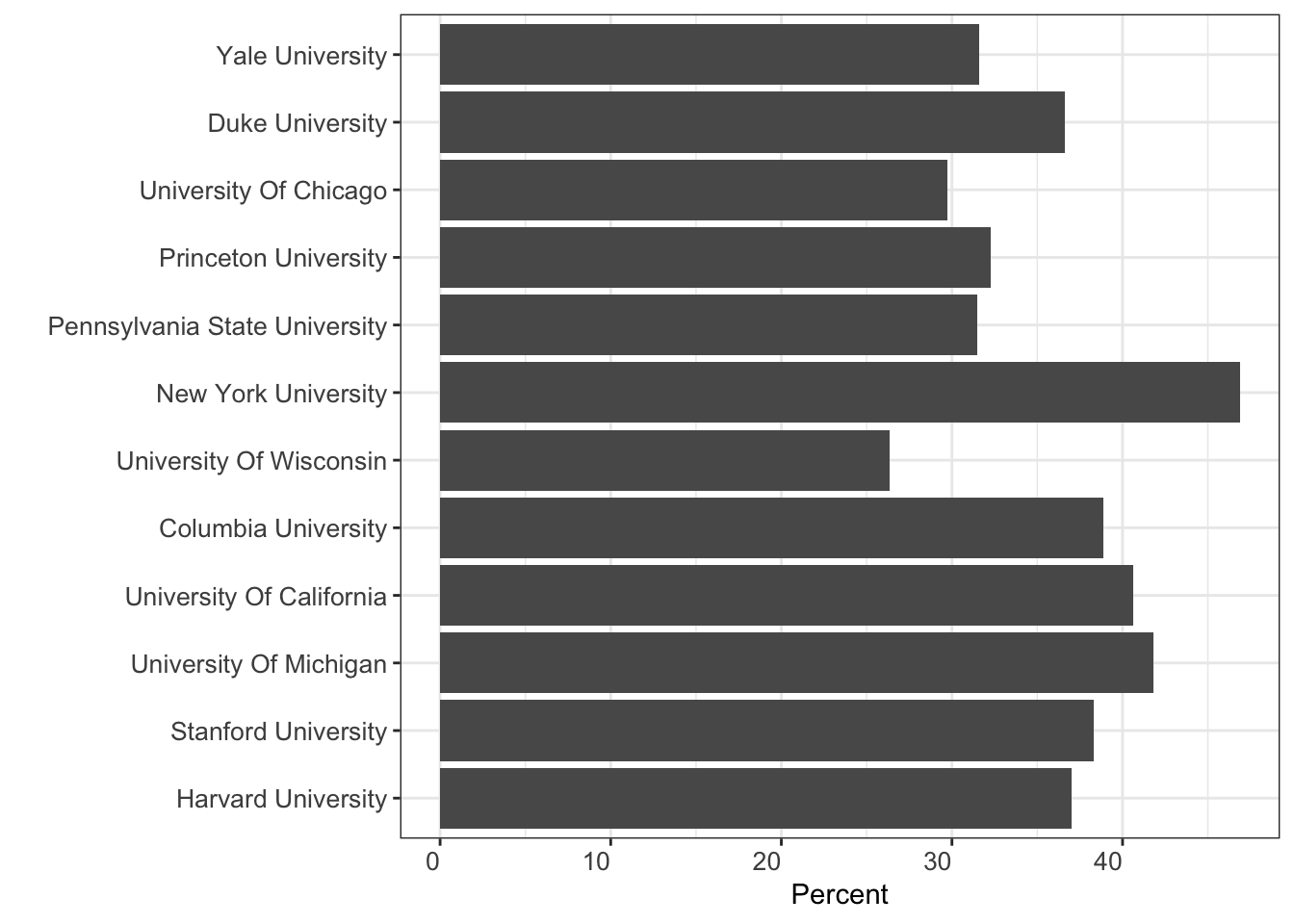

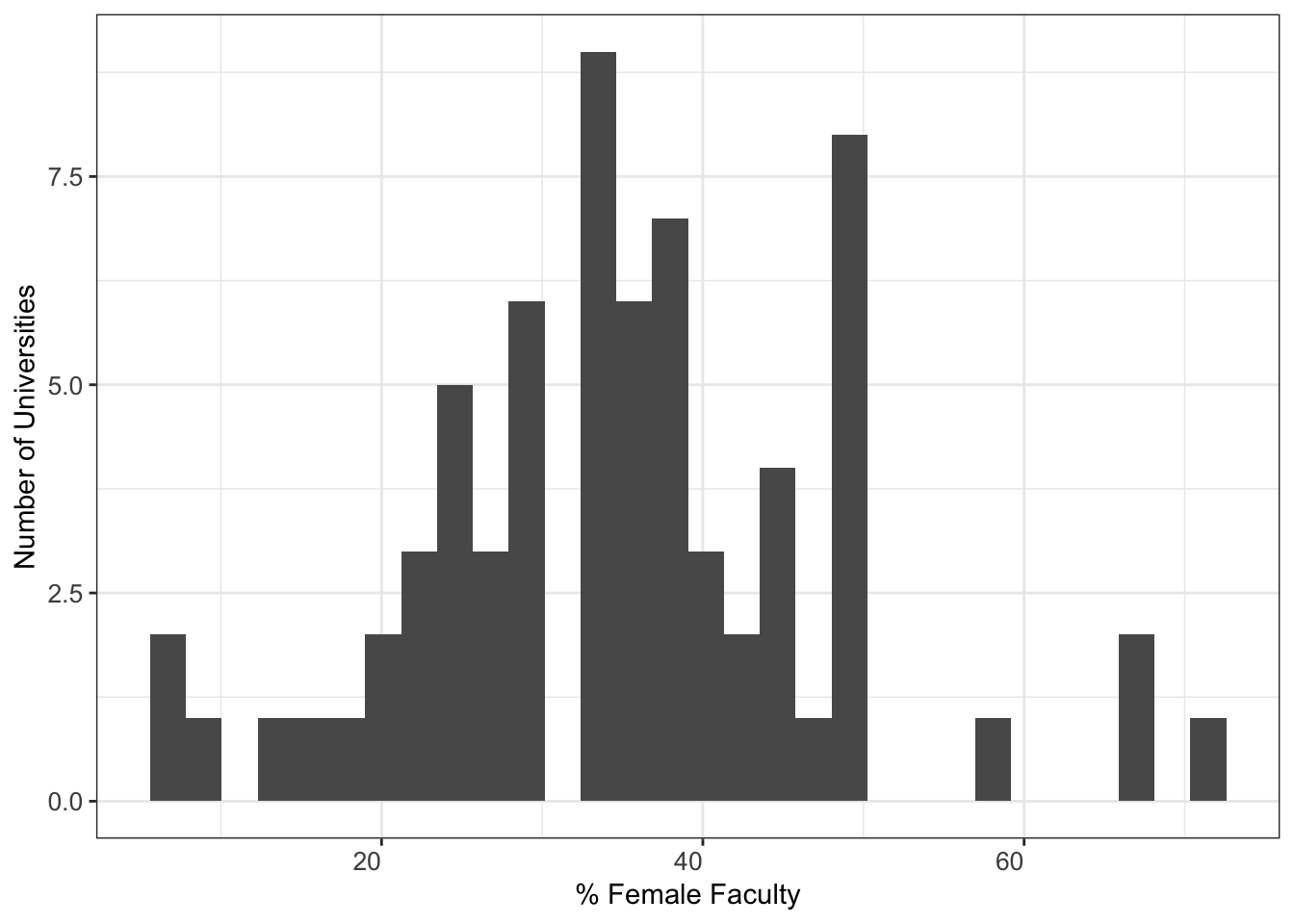

In order to qualitatively control for hiring inequalities, we checked for the gender composition of a sample of Ivy-League sociology departments in 2017. Figure 5.8 shows that these departments hired men dis-proportionally, with the exception of New York University (46.88% of female among faculty members). This is a picture similar to what Sheltzer and Smith (2014) found in the life sciences. Figure 5.9 shows the gender distribution of department members among the top 100 universities, according to the Shanghai ranking. With only a few exceptions, in which women are hired more than men, the gender balance was more favorable to men. This would confirm that in most top universities, hiring and academic success are significantly gendered.

Figure 5.8: Percentage of female faculty members in Ivy-League sociology departments in 2017 (Note that the y-axis lists departments according to the Shanghai ranking with the highest ranked at the bottom) (source: University websites)

Figure 5.9: Share of females of current faculty of sociology in top 100 universities (Shanghai ranking, data on 2017)

5.4 Article content analysis

In order to examine whether women and men have different attitudes of research and so write different articles, we first applied machine learning techniques to article contents, i.e., title, abstract, and keywords. By applying structural topic GLM models, we identified probability distributions of recurrent words in each article with the emergence of certain dominant topics that were shared by similar articles. We detected the top 10 most prominent topics, to map the most important characteristics of the research field.

Table 5.5 shows the most important topics identified by the model and the words having the highest probability to recur in all the content of all articles. Table 5.6 shows certain exclusive words that appeared only in one specific topic, e.g., homophily was a word used only among articles that focused on networks.

Table 5.7 shows all the concepts most frequently used by solo male authors in articles in each of the ten topics, while Table 5.8 shows the same for solo female authors. Results show that men and women seem to look at different aspects even when doing research on similar issues.

| Topic | Word_1 | Word_2 | Word_3 | Word_4 | Word_5 | Word_6 | Word_7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | racial | black | ethnic | segregation | white | race | population |

| 2 | class | crime | law | legal | rights | race | cultural |

| 3 | organizational | work | practices | organization | organizations | management | process |

| 4 | public | religious | social | violence | community | religion | school |

| 5 | human | social | article | states | united | male | female |

| 6 | family | effects | educational | education | life | data | children |

| 7 | gender | labor | market | women | employment | men | womens |

| 8 | economic | income | inequality | countries | growth | welfare | development |

| 9 | political | social | state | movement | organizations | politics | movements |

| 10 | social | network | networks | cultural | theory | status | model |

| Topic | Word_1 | Word_2 | Word_3 | Word_4 | Word_5 | Word_6 | Word_7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | ethnic | segregation | whites | residential | immigrants | hispanic | assimilation |

| 2 | homicide | offenders | classification | interviewers | law | tolerance | citizenship |

| 3 | accountability | lawyers | leaders | conversation | rational | cohesion | formalization |

| 4 | religious | church | pluralism | schools | religiosity | conservative | violence |

| 5 | delinquency | socioeconomics | disorders | male | human | govt | juvenile |

| 6 | cohort | cohorts | adulthood | childhood | children | birth | college |

| 7 | jobs | wage | wages | career | workers | markets | market |

| 8 | welfare | foreign | poverty | investment | growth | economic | countries |

| 9 | movements | protest | mobilization | polity | voting | movement | protests |

| 10 | homophily | network | networks | trust | exchange | generalized | scientific |

## A topic model with 10 topics, 2586 documents and a 8126 word dictionary.

## A topic model with 10 topics, 2586 documents and a 8126 word dictionary.| Word_1 | Word_2 | Word_3 | Word_4 | Word_5 | Word_6 | Word_7 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| topic_1 | factions | japan | treaty | revolution | capitalist | modernist | modernists |

| topic_2 | law | sector | cohesion | recipient | grievances | discourse | agricultural |

| topic_3 | mismatched | lottery | fatherhood | premarital | layer | mortality | mental |

| topic_4 | concern | aged | camping | ireland | historiography | obsolescence | senescence |

| topic_5 | libidinal | charismatic | scientific | dilemmas | concept | literary | theorem |

| topic_6 | embeddedness | workplace | trade | homophily | mississippi | strike | unfree |

| topic_7 | skin | tone | business | enterprises | deindustrialization | ties | arisen |

| topic_8 | subcultural | desegregation | radius | attendance | urbanism | animal | curriculum |

| topic_9 | crisis | ethnology | hospitalization | moral | miscellaneous | aids | care |

| topic_10 | congregations | happiness | brazilian | deficits | felt | recidivism | mto |

## A topic model with 10 topics, 2586 documents and a 8126 word dictionary.

## A topic model with 10 topics, 2586 documents and a 8126 word dictionary.| Word_1 | Word_2 | Word_3 | Word_4 | Word_5 | Word_6 | Word_7 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| topic_1 | commemorating | modernist | passive | food | schema | imprinting | doctrine |

| topic_2 | microfinance | concessions | micromobilization | spatial | protest | marriage | localities |

| topic_3 | desegregation | intent | illegally | eeo | legal | establishments | laws |

| topic_4 | labeling | realism | patrimonial | frontier | illness | invisible | commercialization |

| topic_5 | peer | delinquency | china | relief | layer | micromobilization | tie |

| topic_6 | sharecropping | tuscany | tongue | downsize | tuscan | honor | aviation |

| topic_7 | injustice | polarization | computerization | renewal | ussr | combat | intracohort |

| topic_8 | dictator | unpaid | draft | reciprocity | token | heterosexuality | apartheid |

| topic_9 | bodily | breadwinning | science | substitutes | queer | musical | nuns |

| topic_10 | compulsory | merchants | epistemology | customer | ethic | merchant | insurance |

Figure 5.10 shows an example of difference between solo male and solo female authors when considering articles on segregation and inequality (Topic 7). This indicates that gender could influence authors’ sensitivity towards specific concepts or issues even among specialists working in the same field. Therefore, gender penalties could also orient the attention of the community towards specific issues, so biasing exploration.

Figure 5.10: Gender differences in articles on segregation and inequality (Topic 7)

5.5 Statistical models

In order to test our descriptive findings more robustly, we run a negative binomial model (specifically due to count nature of our data) (Snijders and Bosker 1999; Faraway 2005; Zuur et al. 2009), in which publishing in top journals was first examined as associated with gender. We controlled the effect of Ivy-League departments by embedding each scientist in a crossed membership structure, which included the institution in which the scientist originally received his/her PhD and his/her latest academic affiliation (e.g., Akbaritabar, Casnici, and Squazzoni (2018)). This allowed us to control for the Ivy-League effect in two important stages of each scientist’s academic career. Furthermore, we checked whether the gender penalties were less pronounced over the last decades (pre-post 2000), in which gender inequalities have been under the spotlight in the public debate, also informing institutional policies.

Tables ??, ?? and ?? show that differences are related to individual characteristics (i.e., see fixed effects in our models). When considering group variances (i.e., between the institution which awarded the author’s PhD title and his/her latest academic affiliation), we found minimal effects. The factor having the more robust effect was authors’ accumulated citations. Indeed, Table ?? presents another variant of our multi-level models in which we estimated the influence of gender on accumulated citations of each author. Results confirmed that citations went more preferably to articles in which men were authors.

| Total Publications | Publications before 2000 | Publications after 2000 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Constant | 0.26 (0.04)*** | 0.29 (0.05)*** | 0.28 (0.04)*** | |

| Gender Male | 0.20 (0.04)*** | 0.12 (0.06)* | 0.17 (0.04)*** | |

| AIC | 7743.00 | 2976.32 | 4787.59 | |

| BIC | 7772.04 | 3001.27 | 4814.65 | |

| Log Likelihood | -3866.50 | -1483.16 | -2388.80 | |

| Num. obs. | 2463 | 1086 | 1655 | |

| Num. groups: latest_uni | 444 | 256 | 336 | |

| Num. groups: phd_awarded_university | 329 | 195 | 250 | |

| Var: latest_uni (Intercept) | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.01 | |

| Var: phd_awarded_university (Intercept) | 0.03 | 0.00 | 0.01 | |

| p < 0.001; p < 0.01; p < 0.05 | ||||

| Total Publications | Total Citations | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Constant | 0.26 (0.04)*** | 4.37 (0.08)*** | |

| Gender Male | 0.20 (0.04)*** | 0.18 (0.06)** | |

| AIC | 7743.00 | 28818.42 | |

| BIC | 7772.04 | 28847.47 | |

| Log Likelihood | -3866.50 | -14404.21 | |

| Num. obs. | 2463 | 2463 | |

| Num. groups: latest_uni | 444 | 444 | |

| Num. groups: phd_awarded_university | 329 | 329 | |

| Var: latest_uni (Intercept) | 0.02 | 0.19 | |

| Var: phd_awarded_university (Intercept) | 0.03 | 0.08 | |

| p < 0.001; p < 0.01; p < 0.05 | |||

Finally, we looked at a restricted sample of more prolific, star authors, i.e., those one publishing more frequently in both journals. Among authors who published in both journals, 360 were men, 126 were women. Table ?? shows that publishing more in both journals is positively associated with higher recognition by the community but also that being a man is still significant in terms of prolificacy though not significant when considering recognition (i.e., citations).

| Total Publications | Publications before 2000 | Publications after 2000 | Total Citations | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Constant | 0.12 (0.03)*** | 0.04 (0.05) | 0.12 (0.04)*** | 4.20 (0.07)*** | |

| Gender Male | 0.09 (0.03)** | 0.10 (0.05) | 0.06 (0.04) | 0.04 (0.06) | |

| Star sociologist | 1.16 (0.03)*** | 0.79 (0.05)*** | 0.91 (0.04)*** | 1.35 (0.07)*** | |

| AIC | 6610.52 | 2751.34 | 4310.07 | 28380.56 | |

| BIC | 6645.37 | 2781.28 | 4342.54 | 28415.42 | |

| Log Likelihood | -3299.26 | -1369.67 | -2149.03 | -14184.28 | |

| Num. obs. | 2463 | 1086 | 1655 | 2463 | |

| Num. groups: latest_uni | 444 | 256 | 336 | 444 | |

| Num. groups: phd_awarded_university | 329 | 195 | 250 | 329 | |

| Var: latest_uni (Intercept) | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.16 | |

| Var: phd_awarded_university (Intercept) | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.05 | |

| p < 0.001; p < 0.01; p < 0.05 | |||||

5.6 Conclusions

Mapping all publications in top sociology journals, i.e., AJS and ASR, allowed us to reveal a gender pattern. These prestigious journals seemed to especially favor men and their exclusive co-authorship ties: close to 60% of articles in both journals have been authored exclusively by male authors, alone or in male teams. We did not find relevant differences between the two outlets. Although the situation has improved since 2000, these gender inequalities seem to be persistent even after considering the influence of academic affiliation: again the ‘Ivy-League’ effect greatly benefits only male authors.

As in Teele and Thelen (2017)’s study on publication patterns in political science journals, we found that the conventional standard of collaboration is the solo-male author or all-male teams, whereas women are less involved in co-authorships (Renzulli, Aldrich, and Moody 2000; Moody 2004). However, top journals in sociology seem at least more favorable to cross-gender collaborations than political science journals. Interestingly, we found that women are sometimes in important positions in the co-authorship networks but this does not provide significant advantages when looking at the top more prolific or cited authors, who are almost all men. If we consider only la crème de la crème, i.e., authors publishing more frequently on both journals, we found that gender is less significant at least on recognition (i.e., citations). In any case, this would testify to the fact that gender penalties on publications could reflect a more complex context of institutional stratification, which traces back to unequal admission to elite institutions.

Obviously, estimating whether these unequal achievements are due to certain implicit discriminative practices among the academic élite or the mere consequence of a competitive, “winner takes all” academic market would require more in-depth data and analysis on journal submissions, referees and editors (Østby et al. 2013; Siler and Strang 2014). As suggested by Hancock and Baum (2010) and Sheltzer and Smith (2014), it is also difficult to understand whether these outcomes incorporate endogenous self-selection bias tracing back to education, type of research, funding and career (e.g., González-Álvarez and Cervera-Crespo (2017); Hancock and Baum (2010); Sheltzer and Smith (2014)). Here, disentangling inequalities in publications from endogenous academic excellence formation mechanisms, which typically include nonlinear complex dynamics with potential institutional Matthew effects, would be necessary to assess editorial processes in more detail (Lamont 2009). Examining these differences is also key to discuss the role of diversity in academia (Smith-Doerr, Alegria, and Sacco 2017). Encouraging diversity is beneficial to avoid group thinking and mainstream attitudes (Nielsen et al. 2017), detrimental especially in periods of uncertainty as they reduce epistemological and methodological pluralism.

Our study has certain limitations that need to be considered. First, our data do not cover the entirety of the academic domain, from education to funding and promotion. For instance, as said before, looking only at publications does not help to understand even the gate-keeping role of journal editors, editorial boards and referees (Siler and Strang 2014). Therefore, our results cannot help understand editorial measures that might counterbalance these patterns. Secondly, though here we attempted at providing an explorative analysis on topics, a more in-depth attention to methods could help reveal vicious circles and self-reinforcing distortions in intellectual capital investment, which could point to education and training more than publications (Kahn 1993). In short, women may have fewer chances to be published in these top journals because they do not perform the type of research that these journals prefer and in the specific way they prefer it (Teele and Thelen 2017). Furthermore, the changing demographics of the community and certain cohort effects could also bias our findings (Abbott 2016).

Finally, it is possible that these patterns are less pronounced in average and less competitive journals. In general, the proliferation of journals, the high specialization of certain outlets and the increasing number of online tools and platforms to share and communicate scientific articles have now formed a complex scholarly journal ecology. The richness and diversity of this ecology could help counterbalance these patterns. However, given the hyper-competition that characterizes the current situation of academia and the overproduction of scholarly articles, it is likely that the reputational signal of elite publications will be still important due to collective constraints of selective attention and even by hiring committees at the lower layers of the academic system.

References

Clemens, Elisabeth S, Walter W Powell, Kris McIlwaine, and Dina Okamoto. 1995. “Careers in Print: Books, Journals, and Scholarly Reputations.” American Journal of Sociology 101 (2): 433–94.

Leahey, Erin, Bruce Keith, and Jason Crockett. 2010. “Specialization and Promotion in an Academic Discipline.” Research in Social Stratification and Mobility 28 (2): 135–55.

Long, J Scott. 1992. “Measures of Sex Differences in Scientific Productivity.” Social Forces 71 (1): 159–78.

Grant, Linda, and Kathryn B Ward. 1991. “Gender and Publishing in Sociology.” Gender & Society 5 (2): 207–23.

Edwards, Marc A, and Siddhartha Roy. 2017. “Academic Research in the 21st Century: Maintaining Scientific Integrity in a Climate of Perverse Incentives and Hypercompetition.” Environmental Engineering Science 34 (1): 51–61.

Nederhof, Anton J. 2006. “Bibliometric Monitoring of Research Performance in the Social Sciences and the Humanities: A Review.” Scientometrics 66 (1): 81–100.

Karides, Marina, Joya Misra, Ivy Kennelly, and Stephanie Moller. 2001. “Representing the Discipline: Social Problems Compared to Asr and Ajs.” Social Problems 48 (1): 111–28.

Teele, Dawn Langan, and Kathleen Thelen. 2017. “Gender in the Journals: Publication Patterns in Political Science.” PS: Political Science & Politics 50 (2): 433–47.

Cole, Jonathan R, and Harriet Zuckerman. 1984. “The Productivity Puzzle.” Advances in Motivation and Achievement. Women in Science. JAI Press, Greenwich, CT.

Cole, Jonathan R, and Harriet Zuckerman. 1987. “Marriage, Motherhood and Research Performance in Science.” Scientific American 256 (2): 119–25.

Young, Cheryl D. 1995. “An Assessment of Articles Published by Women in 15 Top Political Science Journals.” PS: Political Science and Politics 28 (3): 525–33.

Cain, Cindy L, and Erin Leahey. 2014. “Cultural Correlates of Gender Integration in Science.” Gender, Work & Organization 21 (6): 516–30.

Lomperis, Ana Maria Turner. 1990. “Are Women Changing the Nature of the Academic Profession?” The Journal of Higher Education 61 (6): 643–77.

Kahn, Shulamit. 1993. “Gender Differences in Academic Career Paths of Economists.” The American Economic Review 83 (2): 52–56.

Sheltzer, Jason M, and Joan C Smith. 2014. “Elite Male Faculty in the Life Sciences Employ Fewer Women.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 111 (28): 10107–12.

Prpić, Katarina. 2002. “Gender and Productivity Differentials in Science.” Scientometrics 55 (1): 27–58.

Heijstra, Thamar, Thoroddur Bjarnason, and Gudbjörg Linda Rafnsdóttir. 2015. “Predictors of Gender Inequalities in the Rank of Full Professor.” Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research 59 (2): 214–30.

Xie, Yu, and Kimberlee A Shauman. 1998. “Sex Differences in Research Productivity: New Evidence About an Old Puzzle.” American Sociological Review, 847–70.

Maliniak, Daniel, Ryan Powers, and Barbara F Walter. 2013. “The Gender Citation Gap in International Relations.” International Organization 67 (4): 889–922.

Renzulli, Linda A, Howard Aldrich, and James Moody. 2000. “Family Matters: Gender, Networks, and Entrepreneurial Outcomes.” Social Forces 79 (2): 523–46.

Moody, James. 2004. “The Structure of a Social Science Collaboration Network: Disciplinary Cohesion from 1963 to 1999.” American Sociological Review 69 (2): 213–38.

Leahey, Erin. 2006. “Gender Differences in Productivity: Research Specialization as a Missing Link.” Gender & Society 20 (6): 754–80.

Leahey, Erin. 2007. “Not by Productivity Alone: How Visibility and Specialization Contribute to Academic Earnings.” American Sociological Review 72 (4): 533–61.

Weisshaar, Katherine. 2017. “Publish and Perish? An Assessment of Gender Gaps in Promotion to Tenure in Academia.” Social Forces, 1–31.

Hancock, Kathleen J, and Matthew Baum. 2010. “Women and Academic Publishing: Preliminary Results from a Survey of the Isa Membership.” In The International Studies Association Annual Convention, New Orleans, La.

Preston, Anne E. 1994. “Why Have All the Women Gone? A Study of Exit of Women from the Science and Engineering Professions.” The American Economic Review 84 (5): 1446–62.

Rivera, Lauren A. 2017. “When Two Bodies Are (Not) a Problem: Gender and Relationship Status Discrimination in Academic Hiring.” American Sociological Review, 0003122417739294.

Ridgeway, Cecilia L. 2009. “Framed Before We Know It: How Gender Shapes Social Relations.” Gender & Society 23 (2): 145–60.

MacPhee, David, Samantha Farro, and Silvia Sara Canetto. 2013. “Academic Self-Efficacy and Performance of Underrepresented Stem Majors: Gender, Ethnic, and Social Class Patterns.” Analyses of Social Issues and Public Policy 13 (1): 347–69.

Brink, Marieke, and Yvonne Benschop. 2014. “Gender in Academic Networking: The Role of Gatekeepers in Professorial Recruitment.” Journal of Management Studies 51 (3): 460–92.

Fox, Mary Frank, and Paula E Stephan. 2001. “Careers of Young Scientists: Preferences, Prospects and Realities by Gender and Field.” Social Studies of Science 31 (1): 109–22.

Leslie, Sarah-Jane, Andrei Cimpian, Meredith Meyer, and Edward Freeland. 2015. “Expectations of Brilliance Underlie Gender Distributions Across Academic Disciplines.” Science 347 (6219): 262–65.

Cech, Erin, Brian Rubineau, Susan Silbey, and Caroll Seron. 2011. “Professional Role Confidence and Gendered Persistence in Engineering.” American Sociological Review 76 (5): 641–66.

Page, Scott E. 2010. Diversity and Complexity. Princeton University Press.

Belle, Deborah, Laurel Smith-Doerr, and Lauren M O’Brien. 2014. “Gendered Networks: Professional Connections of Science and Engineering Faculty.” In Gender Transformation in the Academy, 153–75. Emerald Group Publishing Limited.

Dogan, Mattei, and Robert Pahre. 1989. “Fragmentation and Recombination of the Social Sciences.” Studies in Comparative International Development 24 (2): 56–72.

Nielsen, Mathias Wullum, Sharla Alegria, Love Börjeson, Henry Etzkowitz, Holly J Falk-Krzesinski, Aparna Joshi, Erin Leahey, Laurel Smith-Doerr, Anita Williams Woolley, and Londa Schiebinger. 2017. “Opinion: Gender Diversity Leads to Better Science.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 114 (8): 1740–2.

Misra, Joya, Laurel Smith-Doerr, Nilanjana Dasgupta, Gabriela Weaver, and Jennifer Normanly. 2017. “Collaboration and Gender Equity Among Academic Scientists.” Social Sciences 6 (1): 25.

Light, Ryan. 2013. “Gender Inequality and the Structure of Occupational Identity: The Case of Elite Sociological Publication.” In Networks, Work and Inequality, 239–68. Emerald Group Publishing Limited.

Platt, Jennifer. 2016. “Recent Asa Presidents and ‘Top’ Journals: Observed Publication Patterns, Alleged Cartels and Varying Careers.” The American Sociologist 47 (4): 459–85.

Lengermann, Patricia Madoo. 1979. “The Founding of the American Sociological Review: The Anatomy of a Rebellion.” American Sociological Review, 185–98.

Abbott, Andrew. 1999. “Department and Discipline.” Chicago Sociology at One Hundred.

Lutter, Mark, and Martin Schröder. 2016. “Who Becomes a Tenured Professor, and Why? Panel Data Evidence from German Sociology, 1980–2013.” Research Policy 45 (5): 999–1013.

Light, Ryan. 2009. “Gender Stratification and Publication in American Science: Turning the Tools of Science Inward.” Sociology Compass 3 (4): 721–33.

Bourdieu, Pierre. 1988. Homo Academicus. Stanford University Press.

Wais, Kamil. 2016. GenderizeR: Gender Prediction Based on First Names. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=genderizeR.

Wuchty, Stefan, Benjamin F Jones, and Brian Uzzi. 2007. “The Increasing Dominance of Teams in Production of Knowledge.” Science 316 (5827): 1036–9.

Luke, Douglas A. 2015. A User’s Guide to Network Analysis in R. Springer.

Grimaldo, Francisco, Ana Marušić, and Flaminio Squazzoni. 2018. “Fragments of Peer Review: A Quantitative Analysis of the Literature (1969-2015).” PloS One 13 (2): e0193148.

Snijders, TAB, and Roel Bosker. 1999. “Multilevel Analysis: An Introduction to Basic and Advanced Multilevel Modeling.” London: Sage.

Faraway, Julian L. 2005. “Extending the Linear Model with R: Gerenalized Linear, Mixed Effects and Nonparametric Regression Models.” In. CRC PRESS.

Zuur, AF, EN Ieno, NJ Walker, AA Saveliev, and GM Smith. 2009. “Mixed Effects Models and Extensions in Ecology with R. Gail M, Krickeberg K, Samet Jm, Tsiatis a, Wong W, Editors.” New York, NY: Spring Science and Business Media.

Akbaritabar, Aliakbar, Niccolò Casnici, and Flaminio Squazzoni. 2018. “The Conundrum of Research Productivity: A Study on Sociologists in Italy.” Scientometrics 114 (3): 859–82.

Østby, Gudrun, Håvard Strand, Ragnhild Nordås, and Nils Petter Gleditsch. 2013. “Gender Gap or Gender Bias in Peace Research? Publication Patterns and Citation Rates for Journal of Peace Research, 1983–2008.” International Studies Perspectives 14 (4): 493–506.

Siler, Kyle, and David Strang. 2014. “Gendered Peer Review Experiences and Outcomes at Administrative Science Quarterly.” In Academy of Management Proceedings, 2014:14676. 1. Academy of Management.

González-Álvarez, Julio, and Teresa Cervera-Crespo. 2017. “Research Production in High-Impact Journals of Contemporary Neuroscience: A Gender Analysis.” Journal of Informetrics 11 (1): 232–43.

Lamont, Michèle. 2009. How Professors Think. Harvard University Press.

Smith-Doerr, Laurel, Sharla N Alegria, and Timothy Sacco. 2017. “How Diversity Matters in the Us Science and Engineering Workforce: A Critical Review Considering Integration in Teams, Fields, and Organizational Contexts.” Engaging Science, Technology, and Society 3: 139–53.

Abbott, Andrew. 2016. “The Demography of Scholarly Reading.” The American Sociologist 47 (2-3): 302–18.

A slightly different version of this chapter coauthored with Flaminio Squazzoni with the same title has been published in (Akbaritabar, A., & Squazzoni, F. (2020). Gender Patterns of Publication in Top Sociological Journals. Science, Technology, & Human Values. https://doi.org/10.1177/0162243920941588), (In an earlier version of this chapter we had ethnicity of authors included and the data included 4 top sociology journals (i.e. The Annual Review of Sociology, Social Networks, American Sociological Review and American Journal of Sociology) which are excluded from current version to keep the results as concise and coherent as possible).↩

Application Programming Interface provides possibility to access and use information stored in a remote database through scripts and automatic requests.↩

Note that ASA membership data were not available for some years (i.e., 1982-1998, and 2000). In some of the results that follow, we included only 18 years (1982, 1999, 2001-2016) and excluded a sub-set of author data in our sample to match those years. Note also that according to NSF Survey on Earned Doctorates, a perfect gender balance between doctorates awarded in Sociology was reached since 1994, with women being the majority later.↩

Shanghai global ranking of academic subjects: Sociology. Retrieved from: http://www.shanghairanking.com/Shanghairanking-Subject-Rankings/sociology.html (on 21 September 2017). Information on gender of faculty members was extracted from the university websites on October 6th 2017.↩