Chapter 8 Apendices

8.1 R and Python scripts

All R and Python scripts written during this research project is maintained and updated as a Git repository which is hosted on Gitlab. This repository is a bookdown project which includes text of chapters, data, analysis scripts and report scripts of figures and plots. It is fully reproducible and to request access to code and data to replicate the results, one can contact the author at: https://akbaritabar.netlify.com/

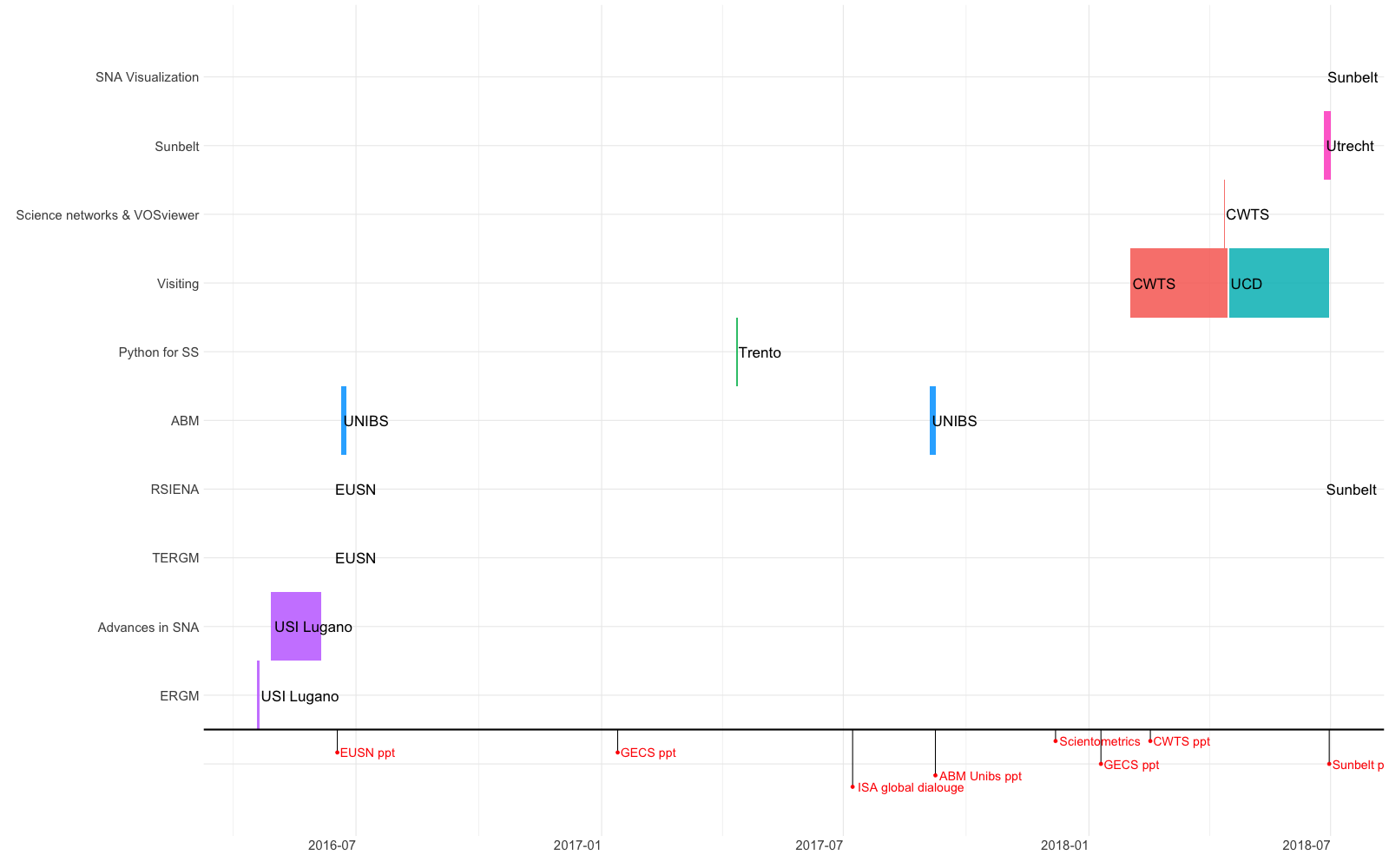

8.2 Timeline of PhD, research visits, schools and presentations

Figure 8.1 shows the timeline of this PhD project including short spring and summer schools, research visits, presentations in conferences and publication dates (designated by lines below x axis).

Figure 8.1: Timeline of PhD research project between November 2015 and September 2018

8.3 Annotated bibliography on social aspect of science

Articles, books, book chapters and online resources we have reviewed (either cited in previous chapters or not) are presented here under specific subjects related to academic work. Author(s) name and year of publication (APA style) is written in Bold in the beginning of each annotation. Parts of the articles we have directly quoted in this annotated bibliography are presented with indentation of paragraphs.

8.3.1 Gender

There are three streams of literature on the issue of lower productivity of females compared to males in science, which is coined as productivity puzzle (Cole and Zuckerman 1984). See also Abramo, D’Angelo, and Caprasecca (2009b)’s note in their review:

- Literature suggesting smaller number of females entering the field (so a self-selection bias like in Sheltzer and Smith (2014) and Hancock and Baum (2010))

- Literature with a feminist tendency suggesting unequal opportunity and sexual discrimination (like case of political sciences in Teele and Thelen (2017))

- Literature with a focus on productivity measurement and explanation mentioning that females perform less than males (based on bibliometric evidences, e.g., case of Italy in Abramo, D’Angelo, and Caprasecca (2009b))

Teele and Thelen (2017)

They look at the publications in 10 prominent political science journals, searching for gender bias and under-representation of females in the pages of these journals. They differentiate between team of authors in paper level analysis, based on gender to all-male, all-female teams, solo male and female authors and cross collaborations. They were not the first in literature to do this gender composition differentiation, there were studies doing so before e.g., Young (1995), Maliniak, Powers, and Walter (2013).

They controlled for share of females in the profession (by APSA association membership) and they observed that the low percentage of female authors (in published papers) does not follow the trend in APSA members.

Coauthorships were more happening among all male teams and when they controlled for research methods, these journals had a tendency to publish more quantitative work rather than qualitative. They claim that is the type of research females are more likely to do (which this tendency has been discussed as a probable self-selection bias or an unconscious structural effect leading females to first take qualitative educational fields and then end up doing this type of research and then lead to have a leakier academic career pipeline (Hancock and Baum 2010)).

Kretschmer et al. (2012)

Authors in this article have tried to test the general notion stating gender bias in science is related to the subject of research. They have studied some of the main gender studies journals to see whether female authors were still under-represented in these journals. They found a strikingly high share of female authors which was not comparable to other journals (e.g., PNAS).

Maliniak, Powers, and Walter (2013)

They claim that after studying journals in political science, while controlling for other variables, articles written by female authors received less citations than articles by males.

They have done a network analysis and found that female authors’ articles were less central in the network of papers citing each other, as a proxy of papers interaction through impact. Male authors tended to cite male authors more, female authors tended to cite female authors less.

This is a cause for concern, If women in IR are systematically cited less than men in ways that do not appear to be associated with observable differences in their scholarship, and if citation counts continue to be used as a key measure of research impact, then women will be disadvantaged in tenure, promotion, and salary decisions.

Young (1995)

She started her narrative by figures of increase in number of females in classrooms in different levels of universities. After she discussed how and where females were publishing their papers in political sciences.

Interestingly she looked at these elements in paper level analysis:

- How frequently females publish?

- How frequently they are single, lead and secondary authors?

- Are percentages consistent across journals and over time?

Length of text and topics of articles by females are compared to those by male authors. It is also used as a potential explanation of the differences in trends of publishing, as working on different subjects. Order of names of authors is studied further in each paper controlling whether it is in or out of alphabetical order.

Membership in national association implies commitment to the profession. The sad conclusion is, because women publish less frequently and because men are unlikely to cite female-authored articles, few women are perceived to be top researchers in the field (Klingemann, groffman, and campagna 1989).

Xie and Shauman (1998)

They reviewed the literature on differences of research productivity between male and female scientists and the puzzle of lower productivity of females. Their answer to this puzzle and if they were able to solve it, is both yes and no.

They have found that females scientists are publishing less because of personal characteristics, structural positions and facilitating resources that are conductive to publication. Beside that, they claim that there is a second puzzle. Puzzle of different career trajectories between males and females in science. Structural resources favor females less. Overall sex differences in research productivity is declined in recent years (until their publication in 1998).

In their regression results, they have a variable as type of current institution which has high quality university to low quality four-year college. This seemed to control for ivy-league effect of institutions.

Prpić (2002)

Participation of females in the labor force and academic labor in Eastern Europe has been higher than Northern America or Western European countries and more equal to males. She mentions that accessibility of scientific career for females in USA has been 22% in 1995. But regardless of higher accessibility, female scientists in East European countries had marginal professional positions.

- Female researchers achieve academic degrees and high(est) academic ranks more rarely and slowly, which makes their qualification structure poorer than the corresponding structure of male scientists

- Female scientists fall behind their male counterparts in other kinds of collegial recognition, as well: employment at prominent universities and other scientific institutions, prestigious scholarships, permanent tenure, scientific awards

- Women hold relatively few positions of influence in scientific institutions: they even hold few supervisory positions in organization units, not to mention running an entire scientific institution

- Exceedingly few female scientists participate in the scientific power structure. This refers equally to their participation in prestigious and influential bodies of national academies, scientific societies, and in advisory and/or editorial boards of scientific journals, i.e., in the bodies that channel scientific development, and in high-level societal and political bodies that design scientific and technological policy

- Women are paid less in science (often for the same job) than their male counterparts

Gender differences in productivity are therefore far from constant and stable. They are sensitive to the time frame, so research should include their trends of development.

Interestingly (page 35), she cites literature that female scientists generally come from higher socio-economic statuses compared to their male counterparts. Since it is harder for them to get into scientific careers than males, so they belong to higher status families and they have different images of scientific career in mind when they start it.

She concludes that although increased productivity of young Croatian scientists is due to the fact that overall number of publications of both male and female scientists increased in the newer generation, but, she finds that the rate and speed of increase in publications in males are higher than females. Males are more ready to adopt to changing system of academia with higher competition:

Men more readily accepted the new standards of scientific production introduced by changes in the system of evaluating scientific work. The theoretic implication of this is that gender differentiation in productivity is not only reflected in the number of publications, but as the different adjustment of scientific performance to new conditions.

In conclusions she emphasizes the results of psychological research:

Psychological research to date indirectly indicates that the smaller productivity of women scientists is socially generated, because no significant differences were found in the intellectual abilities of women and men who enter science, or stay in it. Gender differences in scientific productivity may potentially also arise from insufficiently investigated and identified psychological characteristics – such as personality, motivation, values and interests of male and female scientists – but these seem to be impregnated with cultural and social influences too.

Preston (1994)

Investigates why females tend to leave a scientific career twice more their male counterparts. They mention striking historical numbers from females employment in science:

In 1982, women represented 22 percent of employed natural scientists, 29 percent of employed social scientists, and 3 percent of employed engineers (NSF Resource Series 87-322) (cite: Survey of doctoral recipients. Surveys of Science Resource Series, Washington, DC: National Science Foundation, 1977- 1986)

The conventional explanation that females exit academic (scientific) labor force due to maternity and childbearing responsibilities is incomplete, and they find out that this exit happens more often in early stages of career.

Stack (2004)

This is one of the rare studies that have looked at academics’ children ages and their research productivity to see if having a child (with different ages) can lower the productivity. They have then looked at gender differences for more than 11 thousand PhD recipients hired in academic jobs.

Research on gender and scholarly productivity, the productivity puzzle, has neglected analysis of the influence of children on scientists’ research productivity (e.g., Blackburn and Lawrence, 1995; Keith, 2002; Stack, 1994a, 2002a; Xie and Schuman, 1998, 2003)

They cite two previous studies who have looked at the same subject with data on children and research productivity (in conclusion section):

This finding was consistent with those of two studies from a quarter century ago. Hargens et al. (1978), in a study of 96, married PhD Chemists, found that gender influenced productivity independent of children. Hamovitch and Morgenstern (1977) found similar results, but included PhDs who were not in the paid labor force. Such persons tend not to have the same level of motivation and do not receive rewards publishing as do employed academics.

They found that young children are associated with higher productivity (after controlling covariates of productivity). They mention some limitations (at the end of conclusion), such as flexibility of academic jobs.

Leahey (2006)

Females specialize less in their research activity and this causes (in interaction with gender) for them to have lower research productivity. She claims that during this long history of research on research productivity, specialization has been under-studied and neglected and her study is one of the first to look at its effect. Based on what she found, having a specialized research program and writing papers in the same specialty area repeatedly promotes productivity.

In conclusions:

Men’s and women’s different professional networks and collaboration strategies may also be relevant. Men’s wider and more diverse professional networks (Burt 1998; Kanter 1977) may allow them to find collaborators whose interests overlap their own, allowing their research collaborations to reinforce their expertise in one or a few specialty areas, whereas women’s smaller and more homogeneous professional networks (Grant and Ward 1991; Renzulli, Aldrich, and Moody 2000) require them to branch out to other substantive areas if they want to collaborate, resulting in more diversified research programs.

I found the processes by which specialization mediates gender differences in productivity to be roughly the same in two fields typically neglected by the sociology of science: sociology and linguistics (Guetzkow, Lamont, and Mallard 2004). However, gender effects were more pronounced in sociology - a field with many ill-defined core areas (Dogan and Pahre 1989) - than in linguistics

Abramo, D’Angelo, and Caprasecca (2009b)

They studied gender differences mentioned in literature in Italian academic system and they found that females have lower research productivity. They claim that their study although not focused on the causes of lower productivity of females, have some uniqueness, because it has been done on entire Italian universities on approximately 33,000 scientists. They have classified them based on academic level and scientific field of specialization.

Grant and Ward (1991)

They review sociological publications in three phases, pre-publication, the publication seeking phase and post-publication (citations and notification of works). They conclude that there is little information about how gender politics affect females’ rates of publications and career prospects. They present statistics on the number of females in editorial boards, fundings and coauthorships in sociology journals.

Lomperis (1990)

She first presents figures of how females has entered the labor force and male dominated jobs like law, medicine and university teaching. Then she cites literature on how scholars have looked at this tremendous change of century and how it can change the nature of academic profession. At the same time she cites a work that females are hired for lower positions:

Dr. Benjamin drew on the accumulated data from the AAUP’s annual academic salary surveys and observed that the increased participation of women was “disproportionately in the lower ranks and shows scant evidence of progression through the ranks.”

She asks:

Are women taking over the professions? If so, how? If not, could at least the nature of the professions be changing by virtue of the increasing presence of women in them? The purpose of this article is to address these questions by focusing on one such profession - college and university teaching.

On the notion of “Academic labor market or markets” she mentions:

The reference to academic labor markets in the plural here is deliberate. For as Michael McPherson [21, p. 57] has observed “Ph.D.s are highly specialized personnel. Employment conditions differ very widely among disciplines and even among sub-disciplines.”

In answering her question on “have females changed the nature of the academic profession?”, she claims on the supply side the change has clearly happened. But on the academic ranks and positions which females have occupied, it has happened mostly been on the places were traditionally males were avoiding, such as lower ranked, lower paid positions with not much future prospects. She concludes by mentioning the increasing hardship of following an academic job for both males and females. An advice by academics to young generation; answering survey questions: “don’t do it, this is not a good time”. But she also mentions that increase in females presence in academic positions differs by fields of science. It is higher in humanities and social sciences compared to hard sciences.

Krawczyk and Smyk (2016)

In this study we sought to verify the hypothesis that researcher’s gender affects evaluation of his or her work, especially in a field where women only represent a minority.

They found that gender of author matters for evaluation of a paper, but seemingly not their age. Beside that, they found that this discrimination is not intentional and can be unconscious:

The fraction of guesses that a male-authored paper had been published was 30.6% (14 pct. points) higher than for female-authored ones. If anything, this effect was stronger in female than male subjects. This would represent a clear case of statistical discrimination, in line with the claim of Moss-Racusin et al. (2012) that lack of evidence of (male) in-group favouritism “suggests that the bias is likely unintentional, generated from widespread cultural stereotypes rather than a conscious intention to harm women”

Interestingly, females academic’s outputs could be evaluated lower even by females themselves, which is confirmed in an experiment on students.

Fox and Stephan (2001)

They wanted to compare the objective and subjective image of PhD students toward their career prospects. They found that in certain fields (such as electrical engineering) females have higher hope to get a job as teaching in universities rather than working in industry which might be due to the expectation they have and think that “this is the option open to them”.

Buber, Berghammer, and Prskawetz (2011)

They mention the high childlessness rate of academic females in Austria and Germany. And they want to relate the childbearing behavior of female scientists with their ideals and subjective idea of how many children they want to have. They wanted to analyze whether high childlessness and low numbers of children are intended or not. They claim that several obstacles impede childbearing like: strong work commitment of the female scientists, need to be geographically mobile, high prevalence of living apart together relationships. Female scientist return back to work quickly after they have a child.

Sheltzer and Smith (2014)

Females make up over one-half of all doctoral recipients in biology-related fields but are vastly underrepresented at the faculty level in the life sciences.

They have reviewed data of research institutes websites and counted the number of male and female PhD and post-docs that are hired compared by the gender of supervisor. They have found that male faculty members hire less female graduate students and post-docs than female faculty members did. Then they have separated prestigious (elite) scientists and looked at their hiring behavior too. They have found that male prestigious scientists tend to train less females compared to other male scientists. While female prestigious scientists do not show a gender bias in hiring. They found that new assistant professors of these departments are mostly postdoctoral researchers from these departments, so the above trend gets reproduced in new faculty hiring as well. They comment that this observation might be due to exclusion of females or self selected absence of females.

Renzulli, Aldrich, and Moody (2000)

They studied business start-ups. They conceptualize social capital and compared it between males and females. They found that having more kin and more homogeneity in the network can be a disadvantage for the entrepreneur compared to having more females or being a female entrepreneur.

Cain and Leahey (2014)

They qualitatively study why females are more integrated in some fields (like psychology and life sciences) and less in other fields (engineering and physics) through analyzing accounts of scientific success in these fields.

Kahn (1993)

They have studied females’ progress among PhD academics in the filed of economics and management which is a highly male dominated field.

Many people in corporate and government circles believe that there is a glass ceiling limiting females’ advance to the highest levels of management and professional jobs.

Observing and finding gender differences is good and necessary, and it can signal a discrimination going on, but we can not make sure in explanation unless we look and control for probable self-selection bias by females not to continue an academic career, or different amount of effort and talent (if we can measure it) or differences in educational level or in case of analyzing publications, it can be a discrimination happening by the gatekeeper effect of journal editors and peer review process dysfunctions:

Gender differences might arise because women and men, faced with the same options and opportunities, have made different choices or investments in their careers; or gender differences might arise because of discrimination at some other level, for instance among journal editors and funding sources or during the educational process. Thus, a finding of gender differences in the hiring and promotion of females in a particular academic field is a necessary but clearly not sufficient condition of discrimination, flagging areas of potential concern.

Sotudeh and Khoshian (2014)

They have looked at publications and citations of male and female nano-scientists and have found that although number of female scientists in this field are lower, their research productivity and impact is similar to their male counterparts.

E. B. Araújo et al. (2017)

They have analyzed a sample of 270,000 scientists and found that males are more likely to collaborate with other males, while females are more egalitarian. This holds through different fields and while increasing the number of collaborators each scientist has with the exception of engineering. Considering inter-disciplinarity, males and females behave similarly with exception of natural sciences where females with many collaborators tend to have more collaborators from other fields.

Nielsen et al. (2017)

They start with claiming that teams (working on scientific projects) can benefit from different kinds of diversity, like scientific discipline, work experience, gender, ethnicity and nationality. But they add that it is not enough to add females to the groups and wait for innovation and efficiency to increase, instead they suggest that it is possible to find a mechanism to build up teams with diversity and reach to the optimum outcome. For example:

Women are nearly eight times more likely to lead research projects in biotech firms with flat job-ladders than in more hierarchical academic and pharmaceutical settings.

However, even flat structures are not effective unless the newcomers (women or underrepresented minorities) hit a critical mass, defined as representing between 15% and 30% of team members.

Recruiting women is not enough: Carefully designed policies and dedicated leadership allow scientific organizations to harness the power of gender diversity for collective innovations and discoveries. Put simply, we can’t afford to ignore such opportunities.

Nielsen (2016)

Cross-sectional bibliometric study on 3,293 male and female researchers in a Danish university. Looking at link between gender and research performance. It provides evidence challenging the widespread assumption of a persistent performance gap in favor of male researchers.

Light (2009)

This study reviews prior work on why and how gender inequality affects scientific careers through looking at scientific publications.

Light (2013)

He has studied publications in AJS and ASR looking at organization of science into specialties. He thinks that these organization of sociology into subfields can be a kind of organizational identity which is working toward disadvantage of females.

Using sociological work as a case, these analyses delineate how occupational identities contribute to and differentiate publication success – and thus status hierarchies – for men and women in the field.

Potthoff and Zimmermann (2017)

They are focused on the issue of gender homophily in citations which is mentioned in other articles, that male authors tend to cite male authors more rather than female authors.

Multiple studies report that male scholars cite publications of male authors more often than their female colleagues do — and vice versa. This gender homophily in citations points to a fragmentation of science along gender boundaries. However, it is not yet clear whether it is actually (perceived) gender characteristics or structural conditions related to gender that are causing the heightened citation frequency of same-sex authors.

Since scientists tend to cite people working in their own research area, then differences among male and female scholars and their focus in different research areas plays a role in this citation homophily behavior. And gender homophily in citations is partly due to topical boundaries.

Interesting to note is that in some of these studies the issue is analyzed from a feminist point of view, that males are discriminating against females in a conscious way, and they often provide prescriptive suggestions on how policy makers or activists in science should take action to limit this kind of bias. There are other studies that takes experimental approach and in practice investigates whether there is a bias in evaluating research work of female and male authors. They found that even females were evaluating other female authors’ works lower. They conclude that the bias can be unconscious.

There is studies about human capital stating that the structural forces at work have lead females, from educational point of view, to opt-in for more qualitative specialties and have a different image of themselves. Later, they tend to work in more qualitative fields and subjects which are less central to fields of science and less effective. This causes their works to be valued less and noted less rather than their male counterparts.

Cole and Zuckerman (1987)

This is one of the pioneering studies on the gender differences in research productivity. They were first to call it research productivity puzzle. It is a qualitative study based on interviews with male and female scientists. Both elite scientists and rank and file (normal scientists) are studied. They have asked academics to comment on their own publication trajectory (timeline), adding demographic and life events (e.g., PhD graduation, marriage, child birth and divorce). They tried to explain increases or decreases in the productivity using these life events and academics’ own interpretations.

They claim that females publish less than males, but marriage and motherhood is not the cause. Since they controlled for it and married females with children are publishing equal to their single female counterparts and both of these groups are significantly publishing less than males.

Long (1992)

They wanted to provide a multidimensional, longitudinal description of the productivity differences between male and female biochemists. They observed that sex differences in publications and citations increased during the first decade of the career but are reversed later in the career.

The lower productivity of females results from their over-representation among non-publishers and their under-representation among the extremely productive.

Surprisingly, in comparison to other, they saw that patterns of collaboration is similar between males and females. They found that females’ papers on average gets more citations than males, and their lower overall citations are not due to quality of their papers but due to lower number of papers they publish.

González-Álvarez and Cervera-Crespo (2017)

They have studied 30 neuroscience journals in years 2009-2010 including a total of 66,937 authorships with 79,7 % of the genders being identified that includes 67.1% of male authorships. Surprisingly they observed that females seem to be concentrated as as first author (jonior) position and much less in last (senior) position, which they conclude could be a sign for more participation of females in recent years.

In spite of important advances made in recent decades, women are still under-represented in neuroscience research output as a consequence of gender inequality in science overall.

Paul-Hus et al. (2015)

They claim that social media context can be more gender equal than scientific community which is male dominated. They have looked into the social media metrics to measure impact of research by male and female authors. They wanted to see if impact (as publicity in social media) is different than research impact measured by citations a paper has received. They find significant differences for female authored works impact on social media and they attribute it to male dominance in science compared to more equal context of social media which allows works of female authors to be noticed.

The implications for the use of social media metrics as measures of scientific quality are discussed.

Burt (1998)

He discusses his theory of structural holes and using them to access resources in form of social capital, but he mentions a puzzle, which is the case of females:

The entrepreneurial networks linked to early promotion for senior men do not work for women.

He claims legitimacy could be the reason of this because females are not accepted as legitimate members of the population, and he is developing over the concept of borrowing network of a strategic partner to get access to social capital.

Cole and Zuckerman (1984)

It is different from their other article (Cole and Zuckerman 1987). This is more bibliometric and quantitative analysis of publication histories. They have carefully build up a sample of 526 male and female scientists who received doctorates in 1969-1970 with matched profiles (based on department and time of graduation).

They found that if impact, in terms of number of citation, is compared in a paper by paper basis, females are cited as often or slightly more often than males, but because females publish less, their work has less impact in the aggregate level. They have examined three explanations for gender differences in productivity:

There is no support for the view that women publish less because they collaborate less often than men, when collaboration is measured by extent of multiple authorship. Nor are overall gender differences in citation attributable to gender differences in first authorship, Women are first authors as often as men. Last, there is support for a hypothesis attributing differentials in productivity to differential reinforcement. Women are not only less often reinforced than men, reinforcement being crudely indicated by citations, but they respond to it differently. Women were less apt to maintain or increase their output and more apt to reduce it than comparably cited men at the same levels of prior productivity. Reinforcement has less effect on later output of women than of men. Although gender differences in output and impact are statistically significant, their substantive importance is not self-evident. It is not clear whether observed gender differences signal real disparities in contribution to science. Nor is it clear how productivity should be measured over the course of scientific careers. Questions are also raised about the nature of age, period, and cohort effects at the institutional and societal levels.

T. Araújo and Fontainha (2017)

They have used a network based empirical approach to build up networks of scientific subjects. They have build five categories of authorships:

Our results show the emergence of a specific pattern when the network of co-occurring subjects is induced from a set of papers exclusively authored by men. Such a male-exclusive authorship condition is found to be the solely responsible for the emergence of that particular shape in the network structure. This peculiar trait might facilitate future network analysis of research collaboration and interdisciplinarity.

Rivera (2017)

She focuses on an interesting topic on the gender discrimination in hiring in academic careers and how hiring committees operate. She calls it “relationship status discrimination”. In this qualitative case study, she found that hiring committees infrequently ask about relationship status of male candidates, while they asked frequently about this from female candidates. When the female candidates partner were working in academic or high status jobs the committee consider them not movable and they exclude these candidates when there were viable male or single female alternatives.

Beaudry and Larivière (2016)

Female authored papers receive less citations. They add that authors who write with higher number of female coauthors also receive lower citations. They have analyzed the funding and impact factor of journals and size of collaborative teams. They found also that when females aim for the journals with high impact factors as their male counterparts, their probability of getting cited is lower.

Hancock and Baum (2010)

Similar to other works reviewed:

Numerous studies covering a variety of social and physical sciences have regularly concluded two major things about women and academia: (1) women publish less than men, and (2) women make up declining percentages of the professorate as we move up the ladder from assistant to associate to full professor.

They discuss the two main explanations put forward by literature that possibly females choose to leave academia which is not a welcoming environment for them, or they are being forced out of academia due to their lack of human capital in terms of publications standards and impact measurements which is termed as leaky pipeline for them.

our paper focuses on those women who wish to remain in academia, regardless of how friendly or unfriendly the institutional climate, but do not make it past the assistant professor rank.

They present vast descriptive results of background and demographic information on scientists:

Our 2009 survey of the members of the International Studies Association (ISA) and subsequent analysis addresses this issue in two ways. First, we wanted to see if women are in fact producing at lower rates than men in international studies, as the literature finds happens in many disciplines. Second, we wanted to understand what factors affect publication rates during the assistant professor years. We focused on the assistant professor years because if women do not publish enough early in their careers, they are presumably far less likely to have long-term academic careers. Our findings suggest a variety of ways in which universities might change their policies to better aid assistant professors in achieving research records that will earn them tenure, and in which individual scholars might think strategically about their research and publications.

Barnes and Beaulieu (2017)

They discuss an initiative in political science started to improve females participation through yearly conferences through VIM project (Visions in Methodology). They found that females who attend VIM conference are better networked and more productive in terms of publication.

8.3.2 Diversity

Lamont (2017)

Her essay has 3 parts, in the first part she is focused on moral boundaries in the making of inequality. The second part is focused on exclusion, and part three on academia and academic evaluation and different standards for academic excellence.

In part 3, I argue that in the world of of academia, it is crucial to recognize that different disciplines are best at different things and that they shine under different lights. One model (e.g., the standards of economics) does not fit all, even if the institutionalization of international standards of scholarly evaluation aims to eliminate differences.

She investigates neoliberalism and how US academia and scientific context is more ready and positive towards “Peer Review” because they have been applying its procedures from long ago and they have a lot of players in the academic system in shape of universities and institutions spread over the states. On the other hand Europe and for example France which have a more central scientific system which can have veto power over the Peer review decisions. She mentions her results in her book (Lamont (2009)) and how different academic disciplines can have different evaluation and excellence measurement procedures and values to define worth and who is worthy to be praised and promoted.

Puritty et al. (2017)

They ask a good question about diversity in STEM fields:

Simply admitting an URM student is not enough if that student feels unwelcome, unheard, and unvalued

The current system attracts and retains a relatively narrow range of individuals. Does it produce good scientists? Yes. Does it facilitate a diverse scientific community? Not so much.

8.3.3 Research collaboration (broader views)

Katz and Martin (1997)

They tried to nswer some broad questions such as what is research collaboration, what motivates scientists to collaborate and h_ow to measure collaborations_. They consider coauthorship as a partial measure of research collaborations and they discuss the limitations of it. They review the literature on four different subjects related (or possible to be categorized as sub-groups) of research collaborations.

Laudel (2002)

Based on interviews with scientists they have tried to ask about content of collaboration and build a micro theory of it. They found six models of collaborations. They provide interesting insights about collaborations that do not get rewarded.

8.3.4 Research Productivity

Fox (1983)

They focus on Personality traits of “successful scientists”.

“Aligned with these investigations of personality structure are studies which focus upon the biographical background of scientists. These biographical studies have probed a wide range of items including early childhood experiences, sources of derived satisfactions and dissatisfactions, descriptions of parents, attitudes and interests, value preferences, self-descriptions and evaluations. The aim is to determine the biographical characteristics, experiences, and self-descriptions which differentiate the highly productive and creative, from the less productive and creative, scientist. From these studies, one set of biographical attributes emerges strongly and consistently: eminent and productive scientists show marked autonomy, independence, and self-sufficiency early in their lives. This autonomy is apparent in early preferences for teachers who let them alone, in attitudes toward religion, and in dispositions toward personal relations. In their personal relations, specifically, the creative and productive scientists tend to be detached from their immediate families, isolated from social relations, and attached, instead, to the inanimate objects and abstract ideas of their work. These scientists emerge as ‘dominant persons who are not overly concerned with other persons’ lives or with attaining approval for the work [they are] doing’.” (p 287)

Hargens, McCann, and Reskin (1978)

They have studied whether marital fertility is associated with lower levels of research productivity. Their results show a negative relationship between the two among chemists in USA which holds same for both genders.

Pepe and Kurtz (2012)

It is a PhD thesis focused on networks of coauthorships, communication activity on mailing list and interpersonal acquaintanceship among members of an interdisciplinary modern laboratory. They found a fluid, non-cliquish, small-world like network of coauthorships, that has overlaps in communities building the whole structure between coauthorship and acquaintanceship networks.

Based on this study, he has developed and introduced a digital platform for coauthorship and publications for scientists to collaborate online.

Wootton (2013)

They have an interesting focus on author name(s) order and position in the by-lines of papers and metadata. They explore how it is possible to use this order to weight the contribution of authors to papers, as it is the general practice in hard and natural sciences.

This is the main and starting paper of Abramo and others which they propose their micro economic function to calculate FSS for research productivity. They discuss how it is possible to use this formula to calculate aggregate research productivity in institution, academic disciplinary sector or national levels:

\[FSS_R = \frac{1}{t}\sum_{i=1}^N \frac{c_i}{\bar{c}}f_i\]

Abramo, D’Angelo, and Di Costa (2008)

They added impact factor of journals to the formula of FSS, but only in university level and not in the individual level.

Ellwein, Khachab, and Waldman (1989)

For productivity of authors, beside the number of publications, they take the impact factor of journals and author name position in the by-lines of paper into account:

\[P = \sum_{i=1}^N W_i*Z_i\]

Opthof and Leydesdorff (2010)

They focus on document types (publication types) to calculate the impact of paper by dividing it over the average of impact of that type of publications (e.g., books are compared with citations of all the other books in the sample, article with other articles and reviews with each other)

They added academics’ salary to the calculation of FSS.

Abramo, Cicero, and D’Angelo (2013)

Field of science and academic rank of scientists are added to FSS.

Batista, Campiteli, and Kinouchi (2006)

They introduced a new calculation method for h-index.

Abramo, D’Angelo, and Di Costa (2011) and Abramo and D’Angelo (2014a)

They have used FSS for research productivity measurement. They have tried to compare it between academic ranks.

Barjak (2006)

They have tried to measure computer and internet mediated communication effect on research productivity.

Abramo, Cicero, and D’Angelo (2012)

They used FSS to measur research productivity in two time frames, cross-sectional, and with different scaling and standardization with mean and median. Finally they found that mean of the citation distribution (for the community) is the better measurement strategy.

Egghe (2010)

A review of the literature on h-index and its variants and alternatives.

Bornmann (2010)

They point to skewness of citations distribution and whether to use median or mean to standardize the citations of each publication compared to the community.

Way et al. (2016)

Existing models and expectations for faculty productivity require revision, as they capture only one of many ways to have a successful career in science. They have studied all the professors in 205 PhD granting institutions in USA and Canada in Computer science field. They have a time series view toward all publications in the scientists career. They have used a sensitivity analysis method to investigate the entire career of the scientists, and then define if the number of published papers are decreasing or increasing. Taking a focal point into account, they then compare the slope of the trend of publications counts before and after that change point. They found four different types of trends and they conclude that only 1/4 of the scientists follow the trend that is mentioned mainly in literature, to have an increasing productivity in early career which then decreases.

Leahey (2007)

By looking at two disciplines (including sociology and ASR and AJS journals), this study tries to control for specialization effect on research productivity and earnings and salary.

8.3.7 Fragmentation of sociology

Merton (1942)

Merton’s main article which puts forward the norms of science Universalism, Communism, Disinterestedness, and Organized Skepticism.

Hargens (2004)

He evaluates Merton’s effect in social sciences by looking at the works that cite merton’s papers. He concludes that in order to be an impressive scientist in social sciences, you need to have works that can be cited and notified by differnt sub-communities of social scientists.

Leahey and Reikowsky (2008) and Leahey, Crockett, and Hunter (n.d.)

A primary goal of this paper was to assess how specialization, a defining characteristic of modern science (Dogan & Pahre, 1989, 1990), shapes sociologists’ collaboration styles.

They have chosen 71 coauthored papers from four journals (American sociological review, social psychology quarterly, sociology and education and social science research). They did a mixed quantitative and qualitative (latent profile analysis) on them, to figure out the publication profile of sociologists. A total 21 authors have agreed and participated in their interviews. Their results point to the amount of specialization happened in sociology and how academics can collaborate with each other although these specializations has happened.

Turner (2006)

Turner here mentions what happened to sociology that is so fragmented and incoherent and what can make a discipline cohesive.

Babchuk, Keith, and Peters (1999)

They compare sociology with other disciplines investigating the trend toward more collaborative sciences and coauthorships which is slower in case of sociology and mathematics.

8.3.8 Specialization and promotion

Leahey, Keith, and Crockett (2010)

Their main question in this paper is: What does it take to get tenure in an academic discipline? They have analyzed a sample of sociology PhD graduates and built a measure of research specialization. They found that a high specialization has negative effect on promotion in case of males.

8.3.9 ANVUR and Peer review versus bibliometrics

Marzolla (2016)

This article looked at reports published in ASN (National Scientific Qualification) in Italy. He analyzed the lenght and wordings of the reports and compared them between different academic sectors in Italy concluding that there is no equivalence in quality of the evaluation and reports to candidates which needs to be assessed in future rounds of ASN.

Hicks (2012)

She did and exhuastive literature review on Performance-based university research funding systems in different countries and academic systems. She tries, in one part, to give comparative view on how research evaluation results are effective on the life of researchers.

Marginson and Van der Wende (2007)

Authors review and compare existing rankings of universities, e.g., Times Higher education, and Shanghai ranking. They discuss the shortcomings and advantages of each and they introduce CHE ranking from Germany. At the end they conclude on some necessities that rankings and ranking systems need to meet in order not to bias the purposes and cause goal displacement in academia. They briefly mention the issue of rankings becoming the goal instead of the mean and serving the hyper-competition and quantitative production mantra.

Bornmann, Mutz, and Daniel (2013)

They have replicated and evaluated Leiden Ranking 2011-2012 resutls with a mult-ilevel approach and at the end they have been able to explain some of the differences between the universities by nesting them in their countries. One of their important conclusions is that we need to put country level covarriates in the analysis while looking at universities and provide a ranking of countries. They have also criticised the level of changes publicised by universities when they are able to promote their place in the ranking. They claim if the right confidence interval measures are used, then it is possible to judge whether the changes happened in university’s ranking is significant or not (which is when the Goldstein-adjusted confidence intervals do not overlap).

Claassen (2015)

He has used a Bayesian hierarchical latent trait model to compare results of the eight different university rankings and he concludes that some of these rankings are biased in favor of the universities in their own countries. At the end he presents two of the rankings with lowest bias and highest fairness:

The two unbiased global rankings, from the Center for World University Rankings in Jeddah, and US News & World Report are also the two most accurate.

National research assessment efforts, and how policies like ANVUR in Italy want to evaluate research productivity versus bibliometric assessments and comparing these two methods of evaluation in terms of costs, pros and cons.

They mention six evaluation criteria, briefly:

- Accuracy; The degree of closeness of performance indicators measurements to their true value

- Robustness; The ability of the system to provide a ranking which is not sensitive to the share of the research product evaluated

- Validity; The ability of the system to measure what counts

- Functionality; The ability of the measurement system to serve all the functions it is used for

- Time; The time needed to carry out the measurement

- Costs; The direct and indirect costs of measuring

At the end they conclude that considering cost and time effectiveness of bibliometric evaluations, they can be at least adopted for formal and natural sciences, and for other disciplines like humanities and social sciences, peer review could be the preferable choices.

Abramo, D’Angelo, and Caprasecca (2009a)

This paper which is one of the first works of the authors in the series they have published on research evaluation and assessment. It uses a database of hard sciences in Italy, the whole publications as claimed, to compare peer review results of VTR evaluation with bibliometric evaluation. They conclude (same as in Abramo and D’Angelo (2011a)) which in hard sciences bibliometric methods can be a good approach for evaluation and funds allocation with the pros and cons discussed in the paper.

Boffo and Moscati (1998)

He focused on research evaluation acts in Italy. At the end he is suggesting that one of the different evaluation procedures he suggested need to be selected and put in action in Italy. And this is one of the first works that mentions the tensions in Italian academia after the idea of research evaluation is mentioned. Like the ambiguities in law and decrees. They discuss the role MIUR should play in Italian academic evaluation and pros and cons of having external or internal (or both at the same time) evaluators.

Obviously, an academic that is not accustomed to being evaluated will prefer internal evaluation as the lesser evil

Bertocchi et al. (2015)

They have chosen 590 random papers among 5681 which have been reviewed by ANVUR in VQR 2004-2010. They have compared bibliometric and peer review evaluation of these papers. They have found close and significant agreement between the two methods of evaluation.

They have been focused only on some fields from VQR 2004-2010:

In this paper, we draw on the experience of the panel that evaluated Italian research in Economics, Management and Statistics during the national assessment exercise (VQR) relative to the period 2004–2010.

They clearly mention the difference between blind peer review (the normal peer review) and the “informed peer review” that ANVUR and VQR have applied in their evaluation, which means, refrees are aware of the identity of the authors and where the papers have been already published. This causes some biases in the evaluation and in their results to compare peer review with bibliometric statistics.

In other words, we cannot disentangle whether the correlation that we observe depends on an intrinsic relation or on the influence of the information on publication outlets on the reviewers.

As a consequence of this caveat, we need to be clear about the policy implications that we can draw from our analysis. Particularly, as noted, we cannot make any claim about the validity of bibliometrics as a substitute for peer review, let alone advocating the substitution of the informed peer review process with bibliometric assessments.

The goal of the VQR exercise is to evaluate published work of Italian academics between 2004 and 2010, and therefore this limitation is imposed on us by the very structure and goals of the VQR exercise. Future VQR waves could compare bibliometric analysis and peer review using anonymized published material so that neither the publication outlet nor the name of the authors are revealed to the reviewers.

Franceschini and Maisano (2017)

They have collected and organized the criticisms directed to VQR 2011-2014 (e.g., Boffo and Moscati (1998), then after VQR 2004-2010, e.g., Baccini and De Nicolao (2016), and after VQR 2011-2014 and three next correspondences are here (Benedetto et al. (2017b); Abramo and D’Angelo (2017); Benedetto et al. (2017a)))

They mention three main critical methodological vulnerabilities of the VQR 2011–2014, partly inherited from the VQR 2004–2010, are:

- Small sample of papers evaluated for each researcher

- Incorrect and anachronistic use of journal metrics for assessing individual papers

- misleading normalization and composition of Ci and Ji

We are doubtful whether the whole procedure – once completed thanks to the participation of tens of thousands of individuals, including evaluation experts, researchers, administrative staff, government agencies, etc. – will lead to the desired results, i.e., providing reliable information to rank universities and other research institutions, depending on the quality of their research. We understand the importance of national research assessment exercises for guiding strategic decisions, however, we believe that the VQR 2011–2014 has too many vulnerabilities that make it unsound and often controversial.

Solutions they suggest:

Major vulnerabilities of the VQR 2011–2014 can be (at least partly) solved by (1) extending the bibliometric evaluation procedure to the totality of the papers, (2) avoiding the use of journal metrics in general, and (3) avoiding questionable normalizations/combinations of the indicators in use. Finally, the introduction of the so-called altmetrics could be a way to solve (at least partly) the old problem of estimating the impact of relatively recent articles, without (mis)using journal metrics.

This is an answer to the criticisms raised by Franceschini and Maisano (2017), which mainly considers their critics as not valid or not constructive and they believe authors didn’t read the VQR documents carefully.

They answer the criticisms on small sample of research work evaluated, by saying that asking for all the papers published in the period under study is against the principle of treating all areas equally, and it has never been adopted by RAEs or REF in UK.

To answer use of journal’s impact as a bibliometric indicator they pose three reasons, large number of community under evaluation, recentness of the publications, and use of two bibliometric indicators instead of one.

And for other points on normalization and combination of bibliometric indicators they cite a response on “La Voce” website that they have given recently and they point out that authors didn’t give alternative proposals for the criticisms they raise, i.e., their criticisms are not constructive.

Abramo and D’Angelo (2017)

This a type of comment on answer of Benedetto et al. (2017b) to criticisms of Franceschini and Maisano (2017) which mainly supports the criticisms and tries to show the answers were not sufficient. They start by mentioning that Benedetto et al. (2017b) have seen all the criticisms as “not-constructive” and lacking proposals of alternatives.

They claim that ANVUR staff did not have the necessary knowledge for the evaluation and they were not ready to receive and accept constructive suggestions. So there was a knowledge transfer failure from scientists to practitioners. And they believe that ANVUR previous and current memebers do not have relevant CV and experience to handle a national scale research evaluation exercise.

This is answer of the ANVUR members to Abramo and D’Angelo (2017). They start by stating that Abramo and D’Angelo’s idea of a “Scientometric model of evaluation” that can be applied in different fields of science is a simplistic one and the case of national scale research assessment is more complex and multi-faceted. ANVUR has to evaluate not just research, but also teaching, administrative performance, social impact, student competence etc. which includes hard sciences to humanities and social sciences.

The Italian legislator’s choice not to entrust it to scientometricians, but rather to leading scientists and scholars, competent in different fields and highly familiar with the higher education system in a plurality of countries, has been indeed a wise one. And the fact that Abramo and D’Angelo are not even capable to imagine the scope of such an evaluation, even if one remains within the boundaries of “research” (itself a rather differentiated system, which requires the intimate knowledge of scientists and scholars), is highly indicative of the limited horizons within which they move.

Abramo and D’Angelo continue by asking the rhetorical question “Why did ANVUR then not enforce the ‘equality’ principle in this case, rather than offering bibliometrics for some and not others?”. Even in this case, the answer is very simple: there are scientific areas, such as social sciences, law, humanities, where bibliometrics indicators are totally unreliable.

Whitley (2003)

He discusses the macro level policies which might affect how science and scientific discoveries work, he mentions examples from countries with centralized control, e.g., a ministry, on top of higher education system and academia compared to countries without this type of central agency, such as USA, which tend to show different approaches in solving problems and making scientific discoveries.

Baccini and De Nicolao (2016)

This is another paper which discusses the experiment ANVUR did (mentioned in Bertocchi et al. (2015)) to check for the aggreement between informed peer review and bibliometric analysis of the publications and individual scientists’ productiviy or quality of publications. With this meta-analysis they find out that the results and acceptable and good levels of agreement that ANVUR reported was not right if you consider how to interpret Kappa scores used in the experiment, and they find only one exception of Area 13 which there could be a fair amount of aggreement between the two method of evaluation.

They conclude that agencies should not substitute informed peer review and bibliometric evaluation results, since there is differences between the two and the Italian national assessment case is even more error prone, because they have mixed the two evaluation methods and it has made it impossible to disentangle the causes to say if a higher evaluation means a field had performed better science or it was due to higher percentage of bibliometric evaluation of papers (since based on ANVUR results, bibliometric evaluation was giving higher ranks to papers than informed peer review).

Geuna et al. (2015)

They compare the research assessment initiatives in UK, Italy and other EU countries, including notions of their costs and a brief history of each of the evaluation exercise. They conclude by contrasting two extremely different cases of UK and Italy, where the former has a performance based research assessment in place and the later has followed the UK case, but with more centralized view to research organization, funding allocations and research evaluations. They also point to the hardships of development, implementation and acceptance of a performance-based research funding, discussing the case of UK.

Geuna and Piolatto (2016)

Similar to Geuna et al. (2015), discusses the case of UK and Italy in national research assessment exercises:

European university funding systems have experienced significant changes in the last 30 years. In all countries, non-government funding sources and performance-based competitive allocation systems have increased. The UK and the Italian models would seem to represent two extremes cases; the UK is a more competitive system involving more private funding (about 50% of total university funding), while Italy depends mostly on public funding (about 75% of total university funding) and especially on the central government bulk grant.

Ancaiani et al. (2015)

This is a paper by ANVUR staff and faculty describing the methodology (combination of bibliometric evaluation and peer review) they applied in VQR 2004-10 and results they achieved in university level.

The Italian VQR 2004–10 has been an unprecedented research evaluation exercise, both for its size, having analyzed almost 185,000 research outcomes, and for the adoption of a highly innovative mix of peer review and bibliometric methods. Results obtained have been used by the Italian Ministry and by universities for funds allocation, respectively, at the University and department level.

8.3.10 Scientists geographical mobility

Chinchilla-Rodrı́guez et al. (2017)

In this article authors have gathered publications data from scientists from ten countries that are affected by US travel ban, they look at how authors who had at least one affiliation to one of these countries were collaborating internationally. They wanted to provide basis to give policy advice to politicians on the effects of these kind of travel bans on scientific productivity and collaborations.

Jonkers and Tijssen (2008)

Focused on Chinese scientists working abroad who return to China they found that:

“Analyzing their mobility history and publication outputs, while host countries may lose human capital when Chinese scientists return home, the so-called “return brain drain”, they may also gain in terms of scientific linkages within this rapidly emerging and globalizing research field"

8.3.11 Sociology of Academic labor

Kalfa, Wilkinson, and Gollan (2018)

Authors did in-depth qualitative interviews with academics from a university in Australia that has undergone major reforms in 2007 (e.g., adopting performance based research evaluation system) that has lead to exit of a share of their senior academics. This has been replaced with early career employees. They have focused on how academics react to this increasing managerialism in academia and they have found out that resistance and protest is not that much prevailing among academics. They have used metaphor of game which allows them to consider academics as participants of a game in which they are more and more embedded and they continue to legitimize the game by continuing to play by its rules.

Blume (1987)

This is a collection of articles published as a book and edited by known scientists in scientomertics and sociology of science. It is focused on the idea of how external players and factors can affect and shape production of science. This effect can stem from these external figures being involved in cooperation with scientists, or in case of constraining priorities of what should be studied by science by means of them providing financial support to scientists (i.e., influencing them in priorities).

They cover different aspects of the subject, in reviewing the theoretical positions (e.g., p 3) they mention the distinction that marxist theoretician put between science (“direct knowledge” which “does not contain anything that indicates its social origin”) and research (“tied to social conditions and relations of production”).

In another part (e.g., p 277), they focus on the topic of cooperation between social scientists and political actors and “The Policy-Oriented Social Sciences: The Rush to Relevance” which points to efforts by sociologists after world war II to provide answers to social issues in three cases of Italy, France and Germany, while this did not actually happen, at least not until 1960s. He discusses the different paths social sciences took in each of these countries due to relatively different relationship between scientists and political actors and the level of consolidation and instituionalization the scientific fields had experienced in each of those coutexts.

They frame the idea behind the book and collection of articles (e.g., p 331) as an effort to comparatively study:

“The”bottom up" initiatives of scientists who wanted their research to be more socially relevant and hence had sought collaboration with non-scientific groups"

They mention (p 345):

The traditional picture of internal cognitive criteria versus external non-cognitive criteria fades away, and a two-dimensionality of all the problems related to the science system emerges: between, on the one hand, the social actors intervening in the scientific enterprise, forming coalitions, inter-organizational structures, and arrangements, and the scientists stepping into these relations to mobilize resources or from more idealistic motives; while on the other hand, the substance of the demand is a cognitive reflection of what we might call the proto-scientific mode of a social problem.

When the scientists are “over-powered” in such relations, they ought to resist; when they succumb in such a situation, for example because of resource dependency, they may be distracted from the cognitive goals of their fields, and in the long term their knowledge may be reduced to obsolete expertise.

Musselin (2008)

He starts from work of Mary Henkel and tries to provide the basis of how a sociology of academic work should look like. He provides comparisons and similarities and differences among the studies of academic work which can be similar to dichotomies, like being mertonian, or versus strong programme. He emphasizes that transformation of higher education institutions into managed organizations leads to some questions like: question of situation, condition of work, ways of producing and diffusing knowledge, norms and identities of the academic profession.

Abbott (2000)

In this paper Abbott talks about the probable future of sociology as a field, if it will survive or not:

I realize that there are sociologists in commercial or governmental contexts, but in the United States sociology is dominated by an academic labor market and the training institutions that support that labor market.

He argues that sociology is not as coherently centered around a method, as anthropology is around ethnography. Or it is not as coherently centered around a theory as economics is around choice theory or centered around a topic as political science is around power.

8.3.11.1 Burnout of scientists

Gill (2009)

In this book chapter, author presents many examples of the interviews with academics about their workload. The levels of stress they are experinecing and the notion of fast academia under the effect of neoliberalism which requires academics to be working over time (figures of surveys are presented):

Many academics are exhausted, stressed, overloaded, suffering from insomnia, feeling anxious, experiencing feelings of shame, aggression, hurt, guilt and ‘out-of-placeness’

Hanlon (2016)

This is similar to the issue of fear of missing out which can happen while scientists try to stay up-to-date with ever growing literature (similar to what discussed here) and it causes them stress.

References

Cole, Jonathan R, and Harriet Zuckerman. 1984. “The Productivity Puzzle.” Advances in Motivation and Achievement. Women in Science. JAI Press, Greenwich, CT.

Abramo, Giovanni, Ciriaco Andrea D’Angelo, and Alessandro Caprasecca. 2009b. “Gender Differences in Research Productivity: A Bibliometric Analysis of the Italian Academic System.” Scientometrics 79 (3): 517–39.

Sheltzer, Jason M, and Joan C Smith. 2014. “Elite Male Faculty in the Life Sciences Employ Fewer Women.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 111 (28): 10107–12.

Hancock, Kathleen J, and Matthew Baum. 2010. “Women and Academic Publishing: Preliminary Results from a Survey of the Isa Membership.” In The International Studies Association Annual Convention, New Orleans, La.

Teele, Dawn Langan, and Kathleen Thelen. 2017. “Gender in the Journals: Publication Patterns in Political Science.” PS: Political Science & Politics 50 (2): 433–47.

Young, Cheryl D. 1995. “An Assessment of Articles Published by Women in 15 Top Political Science Journals.” PS: Political Science and Politics 28 (3): 525–33.

Maliniak, Daniel, Ryan Powers, and Barbara F Walter. 2013. “The Gender Citation Gap in International Relations.” International Organization 67 (4): 889–922.

Kretschmer, Hildrun, Ramesh Kundra, Theo Kretschmer, and others. 2012. “Gender Bias in Journals of Gender Studies.” Scientometrics 93 (1): 135–50.

Xie, Yu, and Kimberlee A Shauman. 1998. “Sex Differences in Research Productivity: New Evidence About an Old Puzzle.” American Sociological Review, 847–70.

Prpić, Katarina. 2002. “Gender and Productivity Differentials in Science.” Scientometrics 55 (1): 27–58.

Preston, Anne E. 1994. “Why Have All the Women Gone? A Study of Exit of Women from the Science and Engineering Professions.” The American Economic Review 84 (5): 1446–62.

Stack, Steven. 2004. “Gender, Children and Research Productivity.” Research in Higher Education 45 (8): 891–920.

Leahey, Erin. 2006. “Gender Differences in Productivity: Research Specialization as a Missing Link.” Gender & Society 20 (6): 754–80.

Dogan, Mattei, and Robert Pahre. 1989. “Fragmentation and Recombination of the Social Sciences.” Studies in Comparative International Development 24 (2): 56–72.

Grant, Linda, and Kathryn B Ward. 1991. “Gender and Publishing in Sociology.” Gender & Society 5 (2): 207–23.

Lomperis, Ana Maria Turner. 1990. “Are Women Changing the Nature of the Academic Profession?” The Journal of Higher Education 61 (6): 643–77.

Fox, Mary Frank, and Paula E Stephan. 2001. “Careers of Young Scientists: Preferences, Prospects and Realities by Gender and Field.” Social Studies of Science 31 (1): 109–22.

Buber, Isabella, Caroline Berghammer, and Alexia Prskawetz. 2011. “Doing Science, Forgoing Childbearing? Evidence from a Sample of Female Scientists in Austria.” Vienna Institute of Demography Working Papers.

Renzulli, Linda A, Howard Aldrich, and James Moody. 2000. “Family Matters: Gender, Networks, and Entrepreneurial Outcomes.” Social Forces 79 (2): 523–46.

Cain, Cindy L, and Erin Leahey. 2014. “Cultural Correlates of Gender Integration in Science.” Gender, Work & Organization 21 (6): 516–30.

Kahn, Shulamit. 1993. “Gender Differences in Academic Career Paths of Economists.” The American Economic Review 83 (2): 52–56.

Sotudeh, Hajar, and Nahid Khoshian. 2014. “Gender Differences in Science: The Case of Scientific Productivity in Nano Science & Technology During 2005–2007.” Scientometrics 98 (1): 457–72.

Araújo, Eduardo B, Nuno AM Araújo, André A Moreira, Hans J Herrmann, and José S Andrade Jr. 2017. “Gender Differences in Scientific Collaborations: Women Are More Egalitarian Than Men.” PloS One 12 (5): e0176791.

Nielsen, Mathias Wullum, Sharla Alegria, Love Börjeson, Henry Etzkowitz, Holly J Falk-Krzesinski, Aparna Joshi, Erin Leahey, Laurel Smith-Doerr, Anita Williams Woolley, and Londa Schiebinger. 2017. “Opinion: Gender Diversity Leads to Better Science.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 114 (8): 1740–2.

Nielsen, Mathias Wullum. 2016. “Gender Inequality and Research Performance: Moving Beyond Individual-Meritocratic Explanations of Academic Advancement.” Studies in Higher Education 41 (11): 2044–60.

Light, Ryan. 2009. “Gender Stratification and Publication in American Science: Turning the Tools of Science Inward.” Sociology Compass 3 (4): 721–33.

Light, Ryan. 2013. “Gender Inequality and the Structure of Occupational Identity: The Case of Elite Sociological Publication.” In Networks, Work and Inequality, 239–68. Emerald Group Publishing Limited.

Potthoff, Matthias, and Fabian Zimmermann. 2017. “Is There a Gender-Based Fragmentation of Communication Science? An Investigation of the Reasons for the Apparent Gender Homophily in Citations.” Scientometrics 112 (2): 1047–63.

Cole, Jonathan R, and Harriet Zuckerman. 1987. “Marriage, Motherhood and Research Performance in Science.” Scientific American 256 (2): 119–25.

Long, J Scott. 1992. “Measures of Sex Differences in Scientific Productivity.” Social Forces 71 (1): 159–78.

González-Álvarez, Julio, and Teresa Cervera-Crespo. 2017. “Research Production in High-Impact Journals of Contemporary Neuroscience: A Gender Analysis.” Journal of Informetrics 11 (1): 232–43.

Paul-Hus, Adèle, Cassidy R Sugimoto, Stefanie Haustein, and Vincent Larivière. 2015. “Is There a Gender Gap in Social Media Metrics?” In ISSI.

Burt, Ronald S. 1998. “The Gender of Social Capital.” Rationality and Society 10 (1): 5–46.

Araújo, Tanya, and Elsa Fontainha. 2017. “The Specific Shapes of Gender Imbalance in Scientific Authorships: A Network Approach.” Journal of Informetrics 11 (1): 88–102.

Rivera, Lauren A. 2017. “When Two Bodies Are (Not) a Problem: Gender and Relationship Status Discrimination in Academic Hiring.” American Sociological Review, 0003122417739294.

Beaudry, Catherine, and Vincent Larivière. 2016. “Which Gender Gap? Factors Affecting Researchers’ Scientific Impact in Science and Medicine.” Research Policy 45 (9): 1790–1817.

Barnes, Tiffany D, and Emily Beaulieu. 2017. “Engaging Women: Addressing the Gender Gap in Women’s Networking and Productivity.” PS: Political Science & Politics 50 (2): 461–66.

Lamont, Michèle. 2017. “Prisms of Inequality: Moral Boundaries, Exclusion, and Academic Evaluation.” In Praemium Erasmianum Essay 2017. Amsterdam: Praemium Erasmianum Foundation; Praemium Erasmianum Foundation.

Lamont, Michèle. 2009. How Professors Think. Harvard University Press.

Puritty, Chandler, Lynette R Strickland, Eanas Alia, Benjamin Blonder, Emily Klein, Michel T Kohl, Earyn McGee, et al. 2017. “Without Inclusion, Diversity Initiatives May Not Be Enough.” Science 357 (6356): 1101–2.

Katz, J. S., and B. R. Martin. 1997. “What Is Research Collaboration?” Research Policy 26 (1): 1–18.

Laudel, Grit. 2002. “What Do We Measure by Co-Authorships?” Research Evaluation 11 (1): 3–15.

Fox, Mary Frank. 1983. “Publication Productivity Among Scientists: A Critical Review.” Social Studies of Science 13 (2): 285–305.

Hargens, Lowell L, James C McCann, and Barbara F Reskin. 1978. “Productivity and Reproductivity: Fertility and Professional Achievement Among Research Scientists.” Social Forces 57 (1): 154–63.

Pepe, Alberto, and Michael J Kurtz. 2012. “A Measure of Total Research Impact Independent of Time and Discipline.” PLoS One 7 (11): e46428.

Wootton, Richard. 2013. “A Simple, Generalizable Method for Measuring Individual Research Productivity and Its Use in the Long-Term Analysis of Departmental Performance, Including Between-Country Comparisons.” Health Research Policy and Systems 11 (1): 1. https://health-policy-systems.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1478-4505-11-2.

Abramo, Giovanni, and Ciriaco Andrea D’Angelo. 2011b. “National-Scale Research Performance Assessment at the Individual Level.” Scientometrics 86 (2): 347–64. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-010-0297-2.

Abramo, Giovanni, Ciriaco Andrea D’Angelo, and Flavia Di Costa. 2008. “Assessment of Sectoral Aggregation Distortion in Research Productivity Measurements.” Research Evaluation 17 (2): 111–21. http://rev.oxfordjournals.org/content/17/2/111.short.

Ellwein, Leon B, M Khachab, and RH Waldman. 1989. “Assessing Research Productivity: Evaluating Journal Publication Across Academic Departments.” Academic Medicine 64 (6): 319–25.

Opthof, Tobias, and Loet Leydesdorff. 2010. “Caveats for the Journal and Field Normalizations in the CWTS (‘Leiden’) Evaluations of Research Performance.” Journal of Informetrics 4 (3): 423–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joi.2010.02.003.

Abramo, Giovanni, and Ciriaco Andrea D’Angelo. 2014b. “How Do You Define and Measure Research Productivity?” Scientometrics 101 (2): 1129–44. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-014-1269-8.

Abramo, Giovanni, Tindaro Cicero, and Ciriaco Andrea D’Angelo. 2013. “Individual Research Performance: A Proposal for Comparing Apples to Oranges.” Journal of Informetrics 7 (2): 528–39. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joi.2013.01.013.

Batista, Pablo D, Mônica G Campiteli, and Osame Kinouchi. 2006. “Is It Possible to Compare Researchers with Different Scientific Interests?” Scientometrics 68 (1): 179–89.

Abramo, Giovanni, Ciriaco Andrea D’Angelo, and Flavia Di Costa. 2011. “Research Productivity: Are Higher Academic Ranks More Productive Than Lower Ones?” Scientometrics 88 (3): 915–28.

Abramo, Giovanni, and Ciriaco Andrea D’Angelo. 2014a. “Research Evaluation: Improvisation or Science?” Bibliometrics. Use and Abuse in the Review of Research Performance, 55–63. http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.707.6756&rep=rep1&type=pdf.

Barjak, Franz. 2006. “Research Productivity in the Internet Era.” Scientometrics 68 (3): 343–60.

Abramo, Giovanni, Tindaro Cicero, and Ciriaco Andrea D’Angelo. 2012. “Revisiting the Scaling of Citations for Research Assessment.” Journal of Informetrics 6 (4): 470–79. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joi.2012.03.005.

Egghe, Leo. 2010. “The Hirsch Index and Related Impact Measures.” Annual Review of Information Science and Technology 44 (1): 65–114.

Bornmann, Lutz. 2010. “Towards an Ideal Method of Measuring Research Performance: Some Comments to the Opthof and Leydesdorff (2010) Paper.” Journal of Informetrics 4 (3): 441–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joi.2010.04.004.